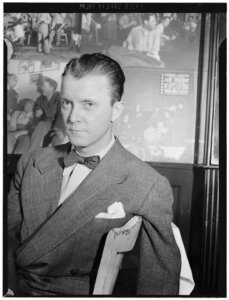

Eddie Condon earned his place in the pantheon of jazz not for his instrumental prowess—he freely admitted he was no more than a solid rhythm guitarist, and he wisely steered clear of soloing—but for his exceptional leadership, business acumen, and visionary drive. He led some of the finest Dixieland ensembles of his time, built a successful career as a promoter and impresario, ran the legendary jazz club that bore his name, and organized a staggering range of concerts, broadcasts, festivals, jam sessions, and recording sessions that helped define the Chicago style and ensure the survival of traditional jazz well into the modern era.

Condon’s popularity soared—DownBeat named him best guitarist in 1942 and 1943, despite the presence of technically superior contemporaries—and he became the public face of white Dixieland and traditional jazz. Yet his real genius lay behind the scenes: as a tireless organizer, a cultural intermediary, and, perhaps most importantly, as a bridge between eras, styles, and races.

Though often linked to the birth and development of the Chicago School, Condon’s legacy extends well beyond it. From the seminal OKeh session of December 1927 to the NBC television special of 1961—essentially the Chicagoans’ swan song—Condon helped shape a tradition that modernized Dixieland without distorting its essence, gently guiding it toward what would come to be known as mainstream jazz. In the face of bebop’s tidal wave, this strategy helped preserve a style that might otherwise have been swept aside.

Yet recognition of his achievements was slow in coming. A dominant critical orthodoxy—led by figures like Alan Lomax, Hugues Panassié, Samuel Charters, and Rudi Blesh—dismissed white Dixielanders as mere imitators, lumping Condon in with revivalist figures like Lu Watters and ignoring the originality and adaptability of the Chicago sound. But Condon and his cohorts (including Bobby Hackett, Joe Marsala, Bud Freeman) were not attempting a faithful resurrection of early jazz. They weren’t antiquarians; they were modernizers, working to expand Dixieland beyond its inherited boundaries, building bridges to the contemporary jazz world rather than burying themselves in its past.

Another overlooked dimension of Condon’s impact was his groundbreaking role in fostering racially integrated groups in an era still mired in segregation. Long before integration became common, he brought Black and white musicians together in clubs, studios, and jam sessions—not just as a political statement, but in pursuit of musical synergy. On 52nd Street and beyond, Condon sought to dissolve barriers and encourage creative exchanges across traditions.

And then there was the writer. Condon authored three books and numerous articles that remain valuable not just as memoir but as critical commentary. In Treasury of Jazz (1957), he shifted away from autobiography to offer sharp insights into the music itself, drawing on writers like Nat Hentoff and Leonard Feather to frame a remarkably perceptive and informed vision of jazz. It’s hard to reconcile the thoughtful cultural commentator with the rakish young man who once abandoned his studies for the ukulele.

Born Albert Edwin Condon in Goodland, Indiana, on November 16, 1905, into a devout Irish-American family, Eddie was the youngest of nine children. His grandfather, David Condon, had emigrated from Ireland; his father John ran a liquor store until the family fled to Illinois in 1907 to avoid Indiana’s prohibition laws.

Eddie’s early years were marked by strict religious rituals: daily prayers, weekly confession, and hymns sung at home by his mother and five sisters. He later described it all—Mass, boarding school, forced piety—as nightmarish. His only relief came in music, and his family provided plenty of it. His brother Jim (or Pat, depending on who’s telling the story) gave him his first ukulele; other siblings played piano or horns. He soon gravitated toward the banjo, then jazz.

By 1921, wearing a brand-new pair of bespoke shoes—a lifelong obsession—Eddie set out for Cedar Rapids to join his older brother Cliff, who helped him land his first professional gig with saxophonist Hollis Peavey. The group played ODJB-style repertoire across the Midwest. In 1923, Condon left for Syracuse, where he met and played with Bix Beiderbecke, forging a lasting friendship. Condon would later help introduce Bix to the Chicagoans—whom he’d soon meet himself.

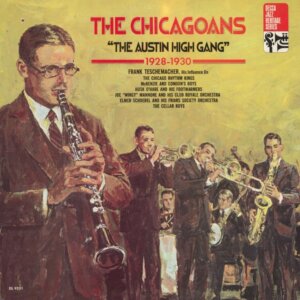

The pivotal encounter came in 1924, when he met the Austin High gang—McPartland, Tough, Freeman, Teschemacher, Lannigan—at a dingy joint called the Cascades Club. “They talked about jazz as if it were a religion just arrived from Jerusalem,” Condon wrote. And he dove right in, joining them on nightly pilgrimages to hear Louis Armstrong at Dreamland, King Oliver at the Plantation, Jimmie Noone at the Apex Club.

Eddie still dreamed of becoming a pianist, and even took lessons. “I wanted to play like Fats Waller,” he said. “But when I first heard Joe Sullivan, whose hands could span a tenth and hold a glass at the same time, I knew it was time to give up.” Around this time he also discovered literature—Proust became a favorite—and romance, though his fleeting relationships with upper-class girls named Barbara and Grace seemed as whimsical as they were brief.

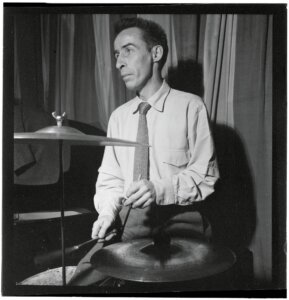

By 1926, the Austin High group had found work as the Husk O’Hare Wolverines, a nod to their mentor and to Bix, their idol. Benny Goodman, Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow, Red McKenzie, Gene Krupa, Muggsy Spanier, and others soon joined the fold. “We were like a new family,” Condon wrote, “united by a desire to make music as exciting as the men from New Orleans.”

The OKeh recordings of December 9, 1927—China Boy and Sugar—marked the official debut of the Chicago School. “We got off to a great start, all together, but each playing his own tune,” Condon recalled. “It was like a package tied with seven ribbons of different colors.” That session—and follow-ups with Liza and Nobody’s Sweetheart—lit a fire under the New York Dixielanders, whose clean but soulless style now seemed pale in comparison.

What distinguished the Chicago sound? Not just Mezzrow’s “flare-up, explosion, shuffle, break,” but a deeper transformation: a new role for the frontline (three-part polyphony led by a soaring clarinet), a relentless forward momentum, the banjo used like a whip, and jazz affirmed as a soloist’s art. The Chicagoans didn’t merely imitate; they innovated, often misunderstood by critics who saw them as flawed mimics of their Black heroes rather than creative forces in their own right.

Though Frank Teschemacher’s clarinet remains the school’s most iconic voice—his modern, jagged lines prompting George Hoefer to compare him to the Free Jazz movement—it was Condon who ensured the music’s longevity. In 1933, sessions like Tennessee Twilight and The Eel continued to evolve the style, while the 1939 Decca album Chicago Jazz, produced by George Avakian, offered a formal statement of its identity: rooted in Oliver and Armstrong, tempered by the NORK and Bix, and propelled by fiery group interplay.

Condon’s leadership of mixed-race bands like the Rhythmakers (1932) furthered his push to integrate traditions and musicians. Landmark sessions like Knockin’ a Jug with Armstrong and Teagarden, or the shimmering Harlem Fuss with Fats Waller, or the daring One Hour with Pee Wee Russell and Coleman Hawkins, offered glimpses of the chamber-like intimacy and emotional range that would come to define mainstream jazz.

The 1930s were difficult. The Depression hit hard. Condon lived in squalid hotel rooms, drank heavily, and underwent the first of many pancreatic surgeries. He worked with Putney Dandridge, Eddie Farley, and the Mound City Blue Blowers, but also found more promising alliances—with Bunny Berigan, Bud Freeman, and McKenzie’s Blue Boys. Freeman’s Windy City Five and Berigan’s I Can’t Get Started remain highlights.

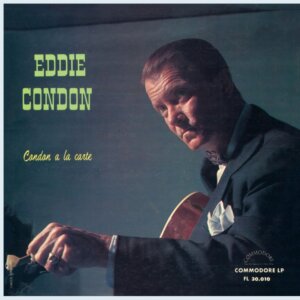

Things began to change in 1936, as swing took hold. 52nd Street exploded with clubs: the Hickory House, the Famous Door, Nick’s, Jimmy Ryan’s. Milt Gabler’s Commodore Music Shop became ground zero for the new traditionalism. When major labels ignored jazz, Gabler recorded it. He gave Billie Holiday a voice for “Strange Fruit” when no one else would. Condon, now engaged to Phyllis and well-connected in the nightlife circuit, became Gabler’s business partner and creative collaborator.

The 1938 Commodore sessions—Love Is Just Around the Corner, Serenade to a Shylock, Embraceable You—marked a turning point. The “Commodore style” preserved Dixieland’s fire but shed its clutter, emphasizing melodic finesse and rhythmic lightness. Swing had filtered in, but not via big bands; rather, through small-group interplay and soloist-forward structures. Condon’s ensemble, with Russell, Freeman, Teagarden, Hackett, Stacy, Shapiro, Wettling, and Tough, became a model of the Dixieland-Swing synthesis.

Jessi Stacy stood out. A pianist of dazzling range and orchestral sensibility, he blended Sullivan’s punch, Wilson’s elegance, and Hines’ drive, and opened new doors for younger players like Gene Schroeder and Stan Wrightsman.

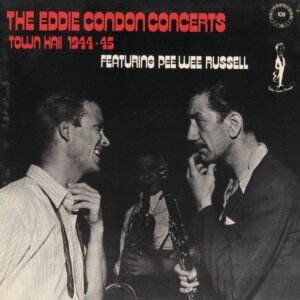

From 1942, Condon organized a groundbreaking series of concerts—at Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, and the Ritz Theater—for the Armed Forces and national radio, featuring giants like Bechet, Ellington, Hines, Waller, and Bunk Johnson. These broadcasts boosted his fame and earned him repeated wins in DownBeat polls.

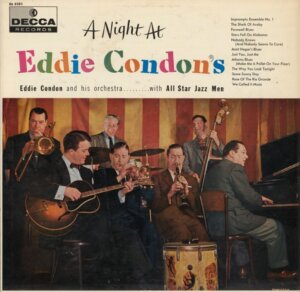

In 1945, he opened Eddie Condon’s Club in Greenwich Village, which quickly became a nexus for traditional jazz—and a cultural hotspot. Celebrities and politicians rubbed shoulders with musicians and critics. Though likely bankrolled by underworld interests (Wild Bill Davison once quipped that Condon was “the only one with a clean record”), Eddie ran a tight ship. His All-Stars—Davison, Cutshall, Edmond Hall, Peanuts Hucko, Schroeder, Wettling—helped him perfect a relaxed yet fiery sound. “If I had to pick a dream band,” Davison said, “I’d pick the same guys.”

The 1950s saw major festival appearances (Newport, 1954 and 1956), a UK tour in 1957, and studio summits in 1959 and 1961 that reunited old Chicago comrades like Krupa, Freeman, Russell, and Teagarden. Yet Condon wasn’t stuck in the past. The best of these sessions looked forward, incorporating musicians from Kansas City (Buck Clayton, Vic Dickenson), arrangers like Dick Cary, and a more modern sensibility. The result? A refined, forward-looking version of Dixieland that prefigured the New Dixieland movement led by Dick Hyman, Bob Haggart, and Bob Wilber.

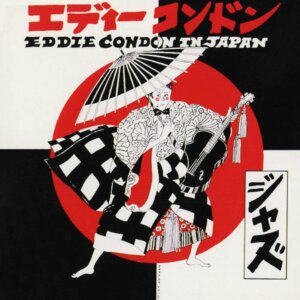

Condon’s artistic zenith may have come in 1964, with a Chiaroscuro-recorded tour of Japan featuring this hybrid lineup. Yet his health was in decline. Years of heavy drinking had taken their toll. Surgeries on his pancreas, stomach, and liver followed. Still, with Davison’s support, he returned to the stage—at a new Condon’s Club on East 56th Street, in duo with Jim Hall, at festivals, on tours, in the studio. His final concert at Carnegie Hall in 1972 was a fitting curtain call.

Eddie Condon died of bone cancer in August 1973, aged 68. His mantle passed to Wild Bill Davison, but his legacy lived on. In 1975, with help from his daughters, a third incarnation of Condon’s Club opened on 54th Street. Alumni like Red Balaban, Ed Polcer, and Tom Artin carried the torch. Yet no revival was needed. Condon was already a legend.

They called him The Indestructible. And that’s how he will always be remembered: guitar in hand, gin within reach, “Liza” playing softly, and that crooked, knowing smile on his face.

by Giorgio Lombardi