A journalist’s toolkit holds no weapons—no arrows or crossbows—but rather a stack of paperwork, press releases, CDs, pitches, a handful of ideas: flickering flashlights to navigate the unknowns of a fleeting encounter, in hopes of forging something meaningful. Often, though, it’s wiser to leave the kit at home and trust in the simple flow of humanity.

This is an unnecessary preamble, perhaps, for returning to Samara Joy in these pages. But it feels right. Joy—both grounded and unbothered by her three Grammys at age twenty-four—reveals a nuanced identity behind her disarming smile and the warmth of her conversation. She tempers the unbearable lightness of youth with intelligence and poise, stepping gracefully into the long and winding river of jazz history, already tangled in its tributaries and estuaries.

“Of course it’s been a long road. All roads that lead where the heart commands are long. But I could see it clearly from the start—mapped out in my mind’s eye, with all its challenges and complications. And still, in some ways, it’s been very simple.”

Joseph Conrad expressed it better, she adds, in three lines. The essence of Samara Joy—born to this sea—is all here.

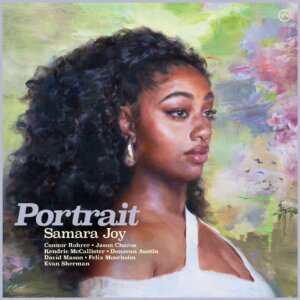

We meet her now with the release of her new album, Portrait, a project in which Samara redraws and redefines the evolving boundaries of vocal jazz across eight tracks. She moves forward—distinct from the past, gesturing toward a future her talent is still learning to shape, even as it relishes the present. As she told Natasha Rothwell in a candid conversation for the New York Times on September 20, success hasn’t dulled her sense of purpose. Rothwell—herself a writer and actress acclaimed for How to Die Alone—shares with Samara a love of improvisation’s liberating force. “It’s going to sound hyperbolic,” Rothwell says, “but improvisation saved my life. You have to trust your instincts, let go of the need for perfection.”

To which Samara responds: “I don’t want to stay in the role of the Grammy winner. I don’t want to spend the next five years doing what people expect of me. I’m twenty-four. I’m in the prime of life, but I already feel like I’ve shifted from where I was at twenty-one. It’s hard to protect myself from all the people—well-meaning—who are trying to shape what they think I should be. But I feel something inside calling me in a direction that aligns with who I really am, and I know I need to follow that voice.”

And so, two years after Linger Awhile and following a year-long world tour, she returned with her band to the sacred Van Gelder Studio. In just a few sessions—three takes per tune—she and her septet (the same group she toured with) opened up new expressive terrain. On tracks like Reincarnation of a Lovebird, Mingus’s tribute to Bird, and the luminous Now and Then, written in honor of her mentor Barry Harris, Joy experiments with form, language, and phrasing.

At its most distilled, Portrait reverses the famous axiom from Lampedusa’s The Leopard: what remains unchanged is the deep identity of jazz itself. What evolves is Samara’s inspired voice—another horn in the section, serving the music, not the spotlight.

What feels new about Portrait?

Oh my goodness—so much! I’ve expanded into lyric writing and jazz composition in ways I hadn’t before. I think my vocal range has grown, and that’s a direct result of playing with this band. Each of us has our own voice, and we pushed ourselves to the limit. That mix of different energies created something unique. More than anything, I’d say this album is about synergy—real connection. There’s a huge difference between walking into a studio with strangers—even brilliant musicians—and playing with people you’ve built emotional bonds with. We built that connection on the road.

Musicians don’t always talk about friendship as a key part of making good music—it’s often framed more as “collaboration.”

I know! But my experience has been different. We spent a year together touring. In that time, you really get to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and the kind of trust that develops is unlike anything else. Sure, in some cases mutual respect is enough. But for me, friendship added a deeper layer—especially in how we listened to each other.

What was it like recording together at Van Gelder?

Incredible. I wanted it to be live, all in one room—because that’s how the best records are made. When we play on stage, we’re not separated by glass or headphones. I wanted that magic in the studio. So we focused on listening—dynamics, balance—without relying on artificial separation. And Van Gelder’s space is designed for inspiration. We tried not to overthink the history—Miles, Coltrane, all of it—but it was humbling. In those moments, that studio became ours.

You said something beautiful recently: “I want to be an artist who remains a student forever.” What does that mean to you?

It might sound like a cliché, but to me it means never stopping. Never settling. Barry Harris lived like that—always searching, always in awe. I met him near the end of his life, and the way he lit up around music… it was like watching a child discover something for the first time. He was almost ninety, playing piano all day, listening, thinking. That’s what being a student means to me. There’s no such thing as “finished.”

Even on YouTube, watching him smoke and talk beside the piano is electric.

Right? He was the most important mentor in my life. And I didn’t even know who he was when I first got to college. I was eighteen; he was close to ninety. He’d lived through decades of jazz history—played with Parker, Henderson, Coltrane. That kind of direct connection is so rare now. Same with Charles McPherson, who told me recently about meeting Bird—what a gentle, generous man he was. Those stories change everything. They ground the music in something real.

Your version of Reincarnation of a Lovebird feels like a direct line from Bird through Mingus to the present. That’s a bold choice.

Very bold. And such a beautiful piece. Mingus didn’t try to imitate Bird—he wrote something emotionally true in his own voice, using almost an opposite language. That makes it even more powerful. It’s not a standard—it’s strange, angular, haunting. I wanted to write lyrics because it moved me so deeply. That song gave me the courage to push myself, to start exploring something beyond writing lyrics for solos, like I did on the first two albums. I wanted to offer a new kind of invitation to the audience—to listen differently.

You also include Barry Harris’s Now and Then. Another lyrical transformation.

Yes! It didn’t have words, so I gave it a story. A way for people to sing it, to live with it. Not necessarily “new,” but seen differently. The album only includes a couple of originals—one by me, one by a bandmate. The rest are reinterpretations, transformed.

There’s also a Sun Ra tune—Dreams Come True—paired with your original Peace of Mind. That combination feels like a thread from Bird to Mingus to Ra.

Exactly! That’s what excites me—the full spectrum, from roots to outer space. Dreams Come True is from one of Ra’s early records. Donovan Austin, our trombonist, played it for me back in school and it stuck with me. Peace of Mind came out of reflecting on the whirlwind of these last two years—suddenly being in the spotlight, navigating leadership, touring, missing home. It’s more of a question than a statement: Where do you find peace of mind? That’s what I want the audience to feel.

You’re from the Bronx—do you still live there?

I visit often, but I’ve moved to Harlem now.

New York feels so charged with beauty and melancholy these days. Do you still see it as the jazz capital?

Honestly, it’s tough. There aren’t many clubs left, and even fewer opportunities to make a living. Touring is expensive. It’s hard to find bands that can sustain that. Jon Faddis, Dizzy’s protégé, told me about touring with Lionel Hampton at nineteen—that kind of experience is almost impossible now. Even Charles McPherson had a day job when he lived across from Coltrane! Today there’s a kind of desperation. You have to use social media just to get noticed. I became a content creator without even meaning to, just to reach people. I’ve been lucky.

Back to Portrait—in tracks like Peace of Mind, there’s a vocal approach that echoes Abbey Lincoln’s use of the voice as another horn in the section.

Yes! Exactly! That’s the heart of the project. I love Abbey Lincoln. On Straight Ahead, she’s not treated as a “feature”—she’s in the band, like another horn. That’s how I hear it. That kind of authenticity is what I aspire to.

Abbey Lincoln and Nina Simone both had a strong commitment to civil rights. Is that something you feel connected to artistically?

Absolutely. Though I’m still figuring out how I want to engage. The world is overwhelming—war, water, food, injustice. I’m aware of the privilege I have to do what I love. I want to give back, whether that’s through music or by supporting causes directly. My songs may not be overtly political yet—they talk about love, growth, change—but I’m trying to find a way to speak from a place of truth.

You’ve surely answered this a thousand times, but—how have the Grammys changed your life?

I never expected to win. I really didn’t. And my first thought afterward was, “Do I need to change now?” But the answer was quick: No. I just need to get back on the road, make another record, sing better, be a better musician. I didn’t want to make another Linger Awhile. I wanted to make Portrait—something bolder.

Look at Miles Davis. He could’ve stayed in cool jazz forever. But that wouldn’t have fueled his creativity. Same with Roy Hargrove—he could’ve been the next Wynton Marsalis, but instead he formed RH Factor, explored Cuban music, hip-hop, everything. That’s what I want—to keep growing.

The aesthetics of Portrait are striking. The single Autumn Nocturne features artwork by Megan Gabrielle Harris; the album cover by Dominic Avant—formerly of Disney—feels vintage and futuristic all at once. Do you see yourself in that visual world?

Yes, totally! That was exactly the point. I wanted something vibrant, layered, emotionally connected to the music—not just a cover with words on it. Dominic did an amazing job. He captured something essential about my identity. Not “the next Sarah Vaughan” or “another Ella Fitzgerald”—just me.

I didn’t make those comparisons—because I don’t like them either.

I get it. But I understand why people make them. They’re a point of reference. Still, I hope Portrait helps people see more clearly who I really am—and who I’m becoming.