The subject is bizarre and pointless: how do you eat sausage skin? Together with the meat or on its own? They were discussing it in a Viennese tavern at the beginning of 1818, a 12-year-old boy and his uncle, not yet 50 years old. Today we know about this conversation because it took place in a very unusual way: the child wrote down what he had to say in a notebook (which has come down to us), because his uncle – who was also his guardian – was completely deaf. The latter, however, answered him verbally, and so the exchange is incomplete for those who read these lines today. We do not know exactly what the adult said, although we can of course guess, because at one point the boy states decisively that “the skin without the sausage is good, but with the sausage it is tastier than the meat alone. The crux of the matter is another: the nephew does not want to give it to his uncle: “If one person is in the habit of doing something in a certain way, can’t another person do it differently?”

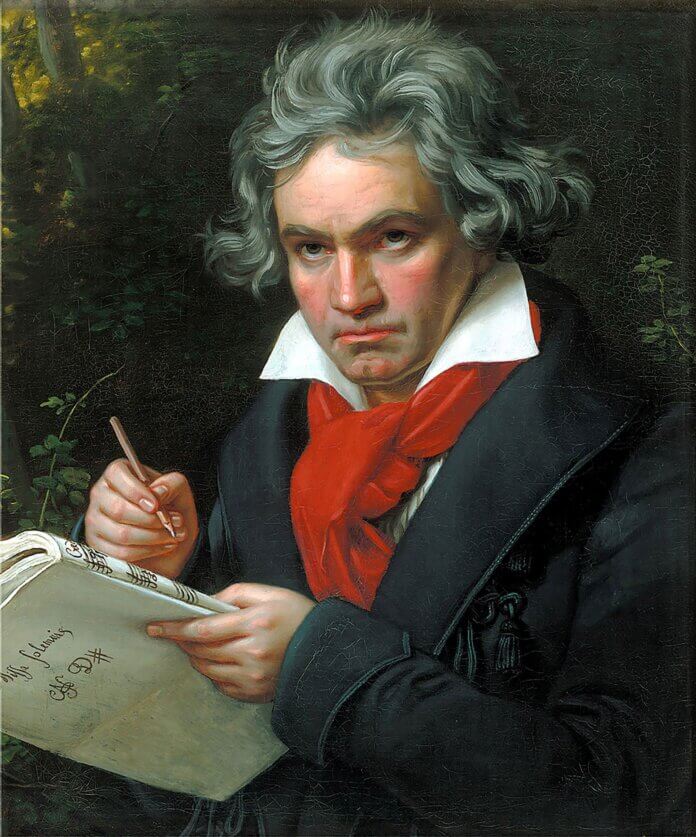

Thus, Beethoven’s first conversation notebook begins with a trivial family quarrel, which, however, is immediately prescient for any reader of a Beethoven biography. It is well known that during the last decade of his life, the composer was largely preoccupied, and not infrequently overwhelmed, by the problems that arose from the guardianship of his nephew Karl, born in 1806, the son of one of his younger brothers who had died prematurely. An issue with multiple and complex implications, including legal ones, in which Beethoven – looking at it with today’s eyes – certainly does not make a good impression. Harsh and oppressive was his intransigence toward his nephew; always evident, and therefore a source of further suffering, was his not only harshly critical, but also vindictive and persecutory attitude toward the young man’s mother, from whom he had decided to take him away. He considered her “unworthy” and of reprehensible, even nonexistent, morality. A prostitute, in short.

The story would end in tragedy many years after that lunch, when the angry nephew allegedly shot himself in the head. And only the disappearance of the musician – on March 26, 1827 – would settle the matter. Thanks to the inheritance left to him by his uncle, Karl van Beethoven would live on his income for the rest of his life (he died in 1858), after having tried many different ways without success. He would marry and have five children, including only one boy named Ludwig.

As for his mother, Johanna Reiss, he would have to wait a century and a half for at least partial rehabilitation by the American musicologist Maynard Solomon, who also theorized how Beethoven’s avowed hatred of his sister-in-law might be a Freudian cover for strong positive emotions. In the mid-1990s, cinema would go further with a forgettable but unique film by British director Bernard Rose called Immortal Beloved. It claims that the anonymous recipient of the famous love letter Beethoven never sent, which was found among his papers after his death, was the despised sister-in-law…

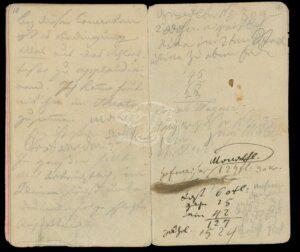

To return to Beethoven’s conversation notebooks, they are in their own way unique biographical documents, at once revealing and of problematic interpretation, often laborious, always insidious, precisely because Beethoven’s “voice” is almost always absent. For this reason, the more than 2,000 letters written during his lifetime remain fundamental and indispensable. Of course, there is no shortage of the composer’s own handwritten remarks, even musical notes, but the bulk of this very considerable bundle of more or less well-assembled papers, consisting of 139 notebooks, offers a constantly interrupted and fragmentary history written by a small group of well-known and lesser-known people. It offers a glimpse into the life lived between 1818 and 1827 in Vienna and a few surrounding towns, but above all in the countless apartments inhabited by the musician, who moved with impressive frequency and never had a house of his own.

On the pages of these small notebooks (usually 12 centimeters wide and 18 centimeters high), domestic and economic problems intersect with reflections on music and literature, theater, life, politics, history and the events of the day. The highs and lows of the existence of a musical genius who decided to use this medium to communicate with his contemporaries, after realizing that his deafness definitely prevented him from doing so naturally or even using more or less sophisticated instruments.

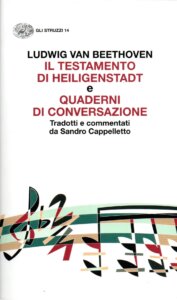

An “as is” translation of the notebooks would be a futile and laborious undertaking. The first to attempt at least a partial edition was Piero Buscaroli, who in 1956 proposed to Leo Longanesi his version of a French translation published ten years earlier by Jacques-Gabriel Prod’homme. The time of the critical edition, begun in the 1970s and completed in Germany only in 2001, was still far off. “You can’t understand anything,” was Longanesi’s response, and the project was shelved. In the early 1960s, while a translation of the years up to 1823 edited by the musicologist Guglielmo Barblan appeared in Turin, the Quaderni di Conversazione became Luigi Magnani’s workhorse: Beethoven in his conversation notebooks was published in 1962 by Ricciardi in Naples, then in 1970 by Laterza and in 1975 by Einaudi. In the meantime, the critic from Reggio Emilia had won the Campiello Prize in 1973 with the novel Beethoven’s Nephew, also published by Einaudi and obviously linked to studies on this central figure in the Notebooks and in Beethoven’s biography.

Since then, however, nothing more has been published until the recent edition, edited and translated by Sandro Cappelletto, again published by Einaudi in the historical Struzzi series. The volume also includes a new translation of a famous Beethoven autograph, the all-too-commonly quoted letter to his brothers, written by Beethoven in the fall of 1802, but never sent, and thus found among the musician’s papers after his death, commonly known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, named after the small town near Vienna where it was written.

The relationship between the two documents is implicit: the testament contains the first and most dramatic confession of the deafness that would plague the musician for the rest of his life, along with the heroic decision not to surrender to fate in the name of art; the notebooks are in many ways the documentation of a supreme artist’s life as a deaf man, accepted and lived with courageous endurance.

Sandro Cappelletto, among other things a well-known voice to the listeners of Rai Radiotre (for whom he produced at the end of 2020 four full-bodied conversations on the subject, which can be found on Rai Play Sound (tinyurl.com/2kw3kexu)), is an author who effectively cultivates the balance between the reasons of popularization and those of rigor and scientific research. Contrary to Magnani, who chose to organize his discourse according to themes supported by the connection with what can be found in the Notebooks (chapters bear titles such as “Social Ideals and Political Passion”, “The Problem of Opera”, “The Two Principles of Sonata Form”, “The Genesis of the Idea and the Missa Solemnis”), Cappelletto’s exploration is strictly chronological, divided by years, up to the last months. The discourse on art and music (including performance problems and piano considerations) is omnipresent, but not exclusive. Rather, what emerges from the reading is a kind of Beethoven diary narrated in between. And in a way, the writer of the notebooks takes on the role of a “chronicler” of current events, be it the Viennese events of the 1920s or the personal and family events of the musician. From this point of view, the list of the most important characters in this particular kind of “human comedy” that Cappelletto sketches out in the Notebooks is both timely and useful.

Besides his nephew, the most important figure is that of Anton Schindler, violinist and conductor, for several years, not without rifts and interruptions, the composer’s main “famulus”, both in practical and medical matters and, above all, in artistic ones. In the latter, moreover, his considerable mediocrity, his real inability to understand Beethoven’s music, is revealed. An inability in which he was in good company: after 1818, in Restoration Vienna and the petty-bourgeois taste known as Biedermeier, Beethoven’s so-called “late style” must have seemed something alien, ineffable and elusive. Only a few sharp and open minds were aware of this, and this is clearly evident in Cappelletto’s narrative, which is rich and precise in linking the texts of the notebooks with cultural and political events, illustrating the creative personalities of the time, and recounting their artistic events.

Schindler is also a central figure in the history of the Notebooks after Beethoven. Given to him as a reward for his assistance to the composer, although they belonged to his nephew Karl, who was the universal heir, the manuscripts were sold, after several years of negotiation (we are now in the mid-nineteenth century), to the Royal Library in Berlin, “to make his pension” (goal achieved: two thousand thalers at once, 400 a year for life). All in all, the notebooks remained in Schindler’s possession for almost two decades, during which time he postponed, “corrected,” cut, censored, and probably destroyed them in several cases. Although it seems implausible (if only for economic reasons, as Cappelletto rightly notes in the volume’s dense introduction) that the suppression affected even more than two hundred notebooks. In this hypothesis, the 136 that were delivered to Berlin would even become about 400, a number that Schindler himself mentioned in his conversations with one of the earliest Beethoven biographers, the American Alexander Weelock Thayer. But the fact remains that, for example, no notebooks exist today for the year 1821, and only two for 1822.

These gaps do not make the journey through the Notebooks any less fascinating for the reader of Beethoven’s last years. In this edition, the editor’s emphases and insights are also useful in capturing the social and political temperament in the capital of the Empire after the Congress of Vienna: A city full of spies, controlled by a conspicuous and suspicious police force, oppressed by a pedantic and omnipresent censorship (about which the poet Franz Grillparzer complained in particular), in which nostalgic Napoleon supporters and “revolutionary” spirits ready to enthuse about the first liberal uprisings that swept the European kingdoms in 1820-21, whose chronicles are followed and discussed with obvious interest, visited the composer’s home (and wrote in his notebooks).

But thanks to Cappelletto, Beethoven’s creative path is just as clear. Beyond the musician’s constant and often confused wrangling with publishers scattered all over Europe on the one hand, and with nobles and crowned heads on the other, in search of unlikely “subscriptions” for future works, these are the years in which the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony, the Diabelli Variations and the last quartets were born, while the last marvelous piano sonatas appeared in print. And it is a pity that the book does not contain, in addition to the index of names, an index of the compositions mentioned, which are numerous and not all as well known as those listed above: it would have been a very useful tool for “navigating” the musician’s creative world.

Beethoven talks about music and thinks in music, listening with his very effective “inner ear”, but he lives in the world. He complains about inflation, resents the government that threatens bankruptcy by making savers lose a lot of money, goes into debt, looks for ways to make the precious bank shares that will allow his nephew to live smoothly, licenses and hires cooks and maids, fights and makes up with his brother, eats and drinks badly, too much anyway, is also treated by four doctors at once, undergoes three home surgeries to remove the fluids produced by the devastating cirrhosis of the liver that will lead him to his grave. Readers of this lively and participatory book will almost feel as if they are witnessing the painful death of the “General of Musicians”, as the visitors who come to his last home, built on the site of the monastery of the “Black Spaniards”, try to reassure him by talking – that is, writing in a notebook – about more or less news in the world of music, about cures for his serious illnesses. Words that are everyone’s heritage, like the art of the genius he could not hear, for whom they were intended.