They really made a good pair, Steve Lacy and his soprano: one as straight as a cube, about six feet tall; the other as straight as a soprano sax, the only one of the “pipe” family to look more like a big cigar. Steve held it forward, slightly off to one side, and between them they formed an almost fixed angle of thirty to forty degrees. Sometimes he would let it sway or rotate as he launched into those circular improvisations that he was a master of and that are among the many things he gave to (his) contemporary jazz, without ever making too many proclamations, because that was how he was, a great gentleman, maybe even a little moody. Sometimes he would treat you with extreme cordiality, and the next time he might barely greet you. That was part of his character: kind but reserved. That doesn’t change the fact that it was impossible not to love him as a whole, beyond admiration for the artist. And to accept with sadness the dismay one feels at the loss of a friend or relative, the news of his death on June 4, 2004, not yet seventy years old, given that he was born – like Steven Norman Lackritz – in New York on July 23, 1934.

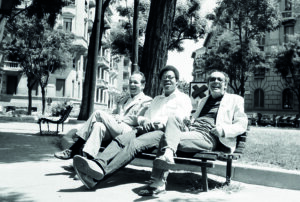

In reality, we Europeans had already lost his familiar and assiduous presence almost two years ago. He had stayed briefly in Italy and then settled in Paris, where he lived for more than thirty years, in rue du Temple (at least that’s where we went to visit him in 1982, where he was welcomed without having given him any advance notice, nor that we had met before). From there, he came to visit us (us Italians, that is) often and willingly. But the last time we saw him, in Syracuse in 2001, after spending some pleasant hours together (apart from his splendid solo recital), he had warned us that his time in Europe was coming to an end: he had been appointed to a professorship at the New England Conservatory in Boston and would be leaving (for good) at the beginning of the next academic year, i.e. in September 2002. What we didn’t know was that we would never see him again, because less than two years later, cancer would take him from us forever.

So here are the two dates – already passed – that, after too much procrastination, convinced us that the time had come to talk about him again: July 23, 1934, June 4, 2004, ninety years and twenty, two intervals in which the existence of one of the most original, rigorous and intelligent musicians jazz has ever known unfolded. Let us set two more chronological markers: seventy and sixty years, between his twenties and thirties, because much is known about Steve Lacy, but about his maturity, while here we want to focus on his younger years, which in themselves are rather emblematic evidence of a decidedly above-average creative curiosity.

But we were talking about instrumental monogamy. In fact, Steve Lacy’s first instrument was the clarinet. He switched to soprano sax at the age of sixteen. “It was a question of love,” he told us during a long conversation after a concert in 1988, from which all the other quotes in the text are taken. “I was struck by this sound and fell in love with it, thanks to Sidney Bechet. On the soprano everything was much more open, at least that was my impression at the time. It was a great advantage because I felt freer to express myself, without constraints. In reality, there is also a disadvantage: without a guide, I had to be the one to lead the way. And maybe people thought I was crazy for choosing such a strange instrument. To be honest, I didn’t realize it at first. I was a little crazy, a little reckless. But later, after I had embraced the new jazz cause, I realized that there were no guides or models, and I began to worry.

We will come back to this passage later. Here we have to start with Steve Lacy’s first steps in traditional jazz, based on the Bechet model. His biographies speak of his association with Henry Red Allen, Pee Wee Russell, Pops Foster, Zutty Singleton, Buck Clayton, Dicky Wells and Jimmy Rushing in the early 1950s. And Dick Sutton, a trumpeter six years his senior, who seems to have recorded only two albums, both in 1954, “Jazz Idiom” and “Progressive Dixieland”, which were brought together in 1986, complete with alternate takes, on the double LP “Avalon – The Complete Jaguar Sessions” (other reissues, even more extensive in chronological terms, have been released over the years), obviously under the name of Lacy, who appears in the sextet that is the protagonist of the recordings (the double CD “Early Years: 1954-1956” by Fresh Sounds, released in 2004, brings together this material with the one we’re about to talk about). The climate is in every way what one would expect. And the sound of the soprano already contains in nuce the stigmata of the Lacy to come: an allusive sound, slightly nasal but clear, bright, very clean.

Lacy returned to the studio in February 1956 to record Ten Matrices, with the quintet/sextet of tenor flugelhorn player Tom Stewart (with Herbie Mann, Dave McKenna, Joe Puma and Al Levitt, among others) playing an absolutely central role, now presents the theme in the first person (as in Rosetta and Gee Baby Ain’t I Good to You) and still places himself on the same level as the leader as a principal soloist, taking another step forward in defining an identity that is already surprisingly mature and recognizable even to those who have only heard the Lacy of his maturity. The olympic progress is striking, light as a film of water, the rigorous internal coherence of each phrase, each note. An artist born adult, as they say in these cases.

Even though there are still traces of Trad, there is a clear Californian coolness in these recordings, typical of the time (and also of various musicians in the group), which is even more evident in the ten tracks recorded two months later (April 13 and 23) by the Whitey Mitchell sextet, arranged by Neal Hefti. Mitchell, the younger brother of the more famous Red, also played the bass on the February tracks, and curiously enough is credited with the entire package, which, along with two (especially swinging) tracks by Joe Puma’s sextet from June 13, 1956, appears on the 2011 American Jazz Classics CD entitled “The Complete Whitey Mitchell Sessions,” also credited to Lacy. Mann (on tenor), Tom Stewart, and then Don Stratton on trumpet and Gus or Osie Johnson on drums are among the other musicians present in dribs and drabs on this additional work. Lacy, for his part, shines with a light all his own.

In the same period, Steve does a triple somersault without a safety net and dives into the music of Cecil Taylor, perhaps not yet the bold and iconoclastic artist he would become a few years later, but still: with the quartet of the free pianist par excellence, he takes part in a recording session in Boston, initially dated September 14, 1956 (three months after the two pieces with Joe Puma), but later brought forward to the previous December 10, thus straddling the two groups of recordings we have just discussed. This detail is not insignificant, but once again it is the man himself who comes to our rescue: “Actually, my first contact with Cecil Taylor and his music was in 1953. It was like being grabbed by the scruff of the neck and thrown into the open sea. Fantastic anyway. Cecil rescued me because I was lost among the antiques. I knew nothing, I was ignorant, I had allowed myself to be fascinated by the classics. I wasn’t wrong, mind you, because I still love the classics and I’m still fascinated by them. But that wasn’t the way I could find myself.

The Boston session, which is part of “Jazz Advance” (Transition), consists of seven pieces, one solo piano, four trios without Lacy, and two quartets. The first piece is Monk’s Bemsha Swing, and it is strange, in light of what we will say shortly, that the soprano does not appear, since she appears immediately after in Charge ‘Em Blues, the first of Taylor’s three themes present, which, as mentioned, is still quite cautious. Paradoxically, the following Azure by Duke Ellington, again a trio, is freer, with some hints of cluster, while Lacy returns for the last time in the second Taylorian theme, the lively, ringing Song (precisely in the part of the soprano that opens it and then hovers intermittently over it, alternating with the piano, which still has periodic openings that are already quite daring). In terms of phrasing, Lacy’s work doesn’t stray too far from what was being proposed in the contemporary New York sessions: fresh, sunny, very adept at navigating above the rhythmic work.

The same quartet, completed by Buell Neidlinger on bass and Dennis Charles on drums, recorded three live tracks at the Newport Festival on July 6, 1957, which were included on the album “At Newport” (Verve), the second half of which was covered by the quintet of Gigi Gryce and Donald Byrd. Billy Strayhorn’s “Johnny Come Lately” opens the program, a favorite of Lacy’s (almost thirty years later he would choose it to open the remarkable “Sempre Amore”, in duo with Mal Waldron), who performs it with the characteristic brightness of her soprano, only a little more pensive in the other two pieces, both by Taylor, Nona’s Blues and Tune 2, showing a growing confidence and fluidity of phrasing throughout, always on the cusp of what is to come.

Another iconoclast of jazz of the time (and for much longer than Taylor, also physiologically by virtue of the many years difference), someone like Thelonious Monk, could not be absent from the Lacy collection, and in this regard the soprano player told us: “He was famous for being mysterious. Yes, it’s true: he was mysterious, like the title of one of his most famous pieces, he was spherical, like his middle name, impenetrable, unassailable. The reality is that he was always silent with those who bored him, with those who made insipid, useless speeches, and apparently there were many, but with us musicians he was open, clear, transparent. He talked to me a lot. Coltrane said the same thing: it depended on who he was with.

Monk would dedicate a large part of his later career to Lacy, to his music, which he pondered for decades, alone or with others, as we will see in these pages. And Monk is the aforementioned trait d’union between Steve and Coltrane. The genius of Hamlet adopted the soprano saxophone precisely because of a meeting between the two (Giuffre, talking about giants again). “John heard me play with Jimmy Giuffre, with whom I worked for a few weeks in 1960. It was my trio, with Buell Neidlinger on bass and Dennis Charles, first, and later Billy Osborne on drums, but in this case Giuffre was the real leader. In New York, he had been very impressed by the new jazz, especially by Sonny Rollins: “He heard him and it was as if he had fallen to the ground. At that point he wanted to change his music completely. He heard me with my trio and thought that this was the right vehicle to find his new way. But he was wrong, because it didn’t work well: there wasn’t a good selection. So we stopped after a few weeks. He took Buell and Osborne, added Jim Hall and moved on. That’s when I became aware of Coltrane and Monk. After the concert, John asked me straight out: “What key is the soprano sax?” “B flat,” I replied. He was astonished. He didn’t know that the soprano was in the same key as his tenor, just an octave higher. He immediately realized that it was the instrument he needed to go higher, to the moon, as he wanted. With the tenor he could go to heaven, but not to the moon! He needed the soprano for that. Two weeks later he was in Chicago playing it. One night Don Cherry called me and said: “I’m in a club in Chicago, listen to this…”. He hung up, and I heard Coltrane on soprano sax for the first time, live from Chicago to New York! An incredible surprise: he was the first to play the new music on soprano after me!

The conversation with its various links has taken us a bit too far: let’s catch up with the intermediate stages. Let us start with another modern jazz guru: Gil Evans. Together with the Canadian musician Steve Lacy, he entered the recording studio for the first time between September 6 and October 10, 1957, for three sessions (the middle one on September 27) that produced the seven pieces for the album “Gil Evans & Ten” (Prestige), on which the clarity with which the soprano saxophonist was now able to handle situations as different as an eleven-piece ensemble, The clarity with which the soprano saxophonist was now able to handle situations as different as an eleven-piece ensemble (with eight winds, including French horn, bassoon and bass trombone, the trademark of the Gilevansian vocabulary, with its soft clouds of sound, and Lee Konitz on alto saxophone), and this in all three tracks on the first side, Remember, Ella Speed and Big Stuff, and again, on the back, in Just One of Those Things and in Jambangle, the only Evans theme on the track list.

On November 1st of the same year, Lacy entered the studio to record under his own name for the first time. The album was called – what do you know – “Soprano Today” (or “Soprano Sax”, Prestige / New Jazz) and he was at the head of a classical quartet with Wynton Kelly on piano and the aforementioned Buell Neidlinger and Dennis Charles. There are six tracks here, none by the soprano saxophonist, but two by Ellington and one by Monk (Work). The tone is still cautious, right from the opening Day Dream, which confirms the lightness, the souplesse (which will never leave him) that the Lacy of the time favored. Later on, the tempos become more lively (in Work, for example, and in Rockin’ In Rhythm, no less, with Charles’ “Latin” style, a trait that is even more evident in Little Girl and Your Daddy Is Calling You), but the essence doesn’t change.

With Mal Waldron and Elvin Jones for Kelly and Charles, Lacy returned to the studio just under a year later, on October 18, 1958, for a work that was decisive in his creative development: “Reflections” (New Jazz), his first monographic album, coincidentally dedicated to Thelonious Monk’s songbook. The twists, the circularity of the phrasing, with less aplomb and more physicality (we’re still talking about the Olympian Steve Lacy), already from the first Four in One reveal how much more than a year had passed, evolutionarily speaking, since ” Soprano Today, in a sign of maturity that is eloquently confirmed by the depth with which the soprano runs through Reflections, one of Monk’s totem themes, not surprisingly taken up repeatedly in the decades to come (often in solo, as we know). Bye-Ya, another big hit, with a Waldron pushed on seductively and perhaps unexplored (how much the pianist will count for Lacy’s future is unknown), Let’s Call This, on similar terrain to Four in One, and the shimmering, lanky Ask Me Now, almost a lullaby taken out of context, represent the other highlights of an exemplary work.

A few months later, in early 1959, Steve Lacy returned to the studio with Gil Evans (with Bill Barber returning on tuba, absent on “Plus Ten”) to record the seven tracks for “Great Jazz Standards” (World Pacific), including a new Monk-esque track, Straight, No Chaser, second on the track list, not coincidentally one of only two (the other being John Lewis’ Django) on which the soprano saxophonist plays a solo, especially with significant thematic repetition. Almost two years would pass before our man would set foot in the studio again, this time to record, on November 19, 1960, “The Straight Horn of Steve Lacy” (Candid), at the head of a unique quartet that included a second saxophone, the complete opposite of the soprano, the baritone of Charles Davis, plus John Ore on bass and Roy Haynes on drums. There are six pieces, none by Lacy, but three by Monk and two by Cecil Taylor (again, the one who’s still in between), plus Donna Lee by Charlie Parker. The language doesn’t seem particularly daring, and the most daring piece, if only because of the obviously very fast staccato, is Donna Lee, while the interweaving of the two saxophones in the obligatos is obviously very pleasant (both, by the way, especially Lacy, with some reed problems).

1961 began (January 10th) with a fleeting appearance, curiously again alongside Charles Davis, on the album “New York City R&B”, dedicated to Cecil Taylor and Buell Neidlinger, as part of the octet completed by Archie Shepp, Clark Terry, Roswell Rudd and Billy Higgins, who recorded the Ellingtonian “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be”. Lacy inserts a short part in which he plays in a curious way in the upper register (those were not the times, not even for him). The year ends with one of the cornerstones of Lacy’s discography (certainly of his early years), namely “Evidence” (New Jazz), together with the trumpeter of the moment, at least in the avant-garde scene, Don Cherry. The album, recorded on November 1 (like “Soprano Today” four years earlier) with Carl Brown on bass and Billy Higgins on drums, contains six tracks, four by the usual Monk (starting with the title track) and one each by Ellington and his right-hand man Billy Strayhorn.

Before we get to the album itself, let’s clarify what we said about Giuffre, Coltrane and Cherry himself in their interactions with Lacy. So: The album that marked Giuffre’s “Rollinsian” turning point is “In Person”, recorded live at the Five Spot in August 1960 with Buell Neidlinger, Billy Osborne (according to Lacy “stolen” by his colleague) and Jim Hall; My Favorite Things, on the album of the same name, the first known example of Coltrane on soprano, dated October 21, 1960 (in fact there is a documented live version from September 24 in Monterey); a few months earlier, between June and July, Coltrane and Cherry recorded “The Avant-Garde,” from which we can deduce that Lacy was writing with Giuffre (“a few weeks,” according to the soprano) when Coltrane and Monk heard it live, probably between late spring and summer 1960. By then, the Don Cherry connection that led to “Evidence” the following year was clearly in place.

But here we are talking about the record in question, whose piano-less line-up and the presence of Cherry (and Higgins) inevitably bring to mind the Coleman Quartet. In reality, as already mentioned, the themes are by other authors and the tone is also very different. It is true that there is a beautiful “active” souplesse, but it is much more vertical (diagonal, if you will) than Ornett’s, which is much more horizontal. So there is a lot of Monk, not only in the improvisational climate that his thematic lines instill in the musicians, but also as a global aesthetic adhesion that Lacy has been embracing for some time, and that Cherry, with his somewhat unhinged approach (more so here than elsewhere), effortlessly embraces. Listen to Evidence, or even a lesser-known track like San Francisco Holiday, and you’ll see what we mean. Lacy is not Ornette: his sovereignty is substantially different, sharper, more bony, also because a certain lyricism is still in the making, which will concern him especially from the eighties on (a gestation that even a rather extreme experimentalism, starting with “The Forest and the Zoo” in 1966 and then in the following decade, will tend to prolong considerably). Paradoxically, the record’s most Ornettian moment comes on the final track, “Who Knows” (by Monk), a decisive break but with a theme quite appropriate to the occasion (and Cherry’s own spin on it).

In 1962, Lacy took part in “Quiet Nights” (Columbia) with Gil Evans’ orchestra, as is well known, everything was in the trumpet of Miles Davis, after which, in March 1963, he was at the Phase Two Coffee House alongside another musician who would often be his neighbor in the future (for example around another luxury outsider, Herbie Nichols, who had studied assiduously since those years), Roswell Rudd, master of the trombone, plus Henry Grimes on bass and Dennis Charles on drums, for what would be his second Monk album. The future is a must, as the album “School Days” would only see the light of day in 1975 thanks to Emanem. It contains seven of the most important Monk pieces (longer than the previous ones: 54′ 37″), in the following order Bye-Ya, Brilliant Corners, Monk’s Dream, Monk’s Mood, Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are, Skippy and Pannonica. The soprano/trombone mix is very happy (also because of the differences between the two musicians, with Lacy already trying some daring moves outside the regular pattern, for example in Brilliant Corners). To choose between all these delicacies would be heresy. Simply a masterpiece, a decisive leap forward to a maturity that now seems inevitable.

At the end of the year (December 30th) the umbilical cord is finally cut: Steve Lacy is in the orchestra that records “Big Band and Quartet in Concert” (Columbia) by his majesty himself, the ineffable Thelonious. Between the original vinyl edition and the following double CD (more than one hour and three quarters of music) there are many gems from the Monk songbook, from Bye-Ya to I Mean You, Evidence and Epistrophy, Misterioso and Four in One… But the soloists called to the center of the stage are others (specifically Thad Jones and the members of the quartet), and Steve stays quietly in the section, occasionally noticeable (for example, in Four in One and in the final reprise of Epistrophy). Instead, his soprano is in evidence a few months later, between April and May 1964, in the lap of the great mother trad, for a tribute to Louis Armstrong by Bobby Hackett’s septet (“Hello Louis!”, Epic).

So we have to meet up with Gil Evans again to complete our itinerary, since the three recording sessions that produced the album in question, the pivotal “The Individualism of Gil Evans” (Verve), ended on July 9, 1964, just two weeks before Steve Lacy turned thirty (the other two sessions date back to September 1963 and April 6, 1964). It should be noted that the CD version of the album, over 68 minutes long where the original LP was half that length, includes five tracks without Lacy, who therefore appears on the opening Barbara Song by Brecht/Weill, in the splendid pastel colors so dear to (and characteristic of) Evans (with flutes and horns in the spotlight and a central solo entrusted to Wayne Shorter’s tenor), Evans wrote the next three tracks, in order, Las Vegas Tango, again with his colors and that Spanish inflection that often characterized his music, the diptych Flute Song/Hotel Me (the latter actually co-written with Miles Davis), with its tendency toward more lively dynamics, and El Toreador, with Johnny Coles’ trumpet at the center of the action. Besides Shorter and Coles, the musicians involved include Frank Rehak, Julius Watkins, Bill Barber, Jimmy Cleveland, Eric Dolphy, Jerome Richardson, Kenny Burrell, Gary Peacock, Richard Davis, Milt Hinton and Elvin Jones, bearing in mind that this is essentially (almost statutorily, one might say) choral music, into whose folds Lacy’s soprano also creeps, without ever coming to the fore. Which will happen to him a lot in the near future, because the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra is coming, and then Rome, Milan, Buenos Aires and finally Paris. Another story, yes, perhaps to be told next time.