Among the comments on YouTube beneath the official video for Pretty World, one of Sérgio Mendes’ most enduring hits, there’s a particularly striking anecdote: “I saw Sérgio Mendes & Brasil ’66 when I was on military leave, in October 1967, before I left for my first tour in Vietnam. My girlfriend got us front-row tickets. Best concert I’ve ever seen.” The commenter goes on to recall a fifteen-minute conversation he shared with singer Lani Hall over a drink—and how, when she left, he pocketed the straw she had used as a lucky charm. His story is followed by nearly eighty responses, many of them thanking him for his service in the war.

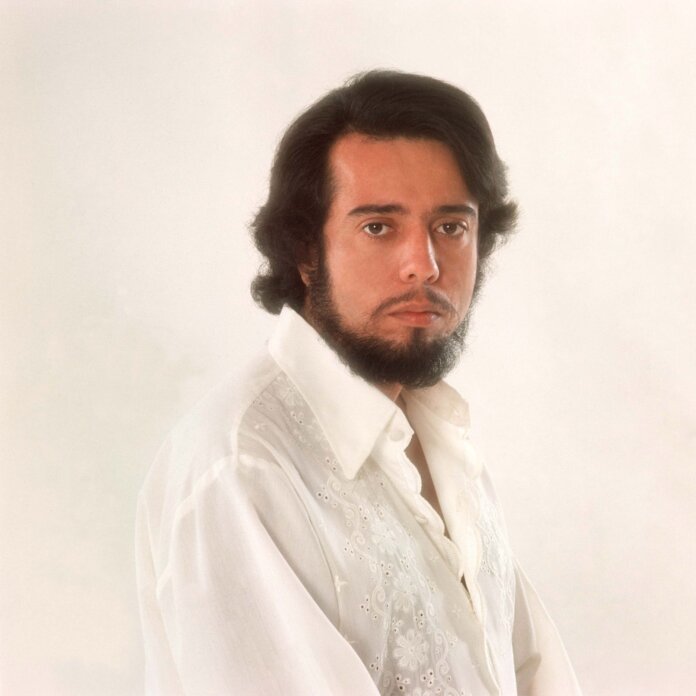

Patriotic overtones aside, what’s striking is that even the music of Mendes could matter deeply to young Americans at a time we typically associate with very different sounds: The Doors, Bob Dylan, Buffalo Springfield, Marvin Gaye. Like it or not, Sérgio Mendes—who passed away on September 5 at the age of 83—embodied, throughout his career, a utopian realm of kindness and warmth, a welcoming, comforting world, touched perhaps only by a veil of melancholy. His music sprang from the same wellspring that nourished Antônio Carlos Jobim, João Gilberto, and the rest of the Bossa Nova vanguard—but with an added carefree spirit that resonated especially with mainstream, often WASP, American audiences.

Mendes’ period of greatest popularity came in the latter half of the 1960s, when he developed the Sérgio Mendes & Brasil ’66 formula in collaboration with producer and lyricist Richard Adler. It was a savvy operation, perfectly pitched, and remains one of the most successful syntheses of American pop and the “new sound” from Brazil—already deeply inflected with jazz. The formula was simple yet ingenious. Mendes added two American singers to his Brazilian trio, making the music more palatable for the U.S. market. He was also fortunate to audition 19-year-old Lani Hall, who became the group’s linchpin. (Dom Um Romão, later of Weather Report, also played drums and percussion with the band for a stretch.) Although the singers generally performed in unison, solo moments were almost always given to Lani. She may have had less stage presence than her counterparts—Bibi Vogel, Janis Hansen, and the sultry Karen Philipp—but her vocal charisma, emotional intensity, and technical command were nothing short of Streisand-worthy.

The Brasil ’66 formula also shined in repertoire. Mendes wasn’t a composer, but he was a brilliant reinterpreter: Bacharach, the Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, Henry Mancini, Cole Porter—no song was off-limits. To these he added Brazilian compositions, often adorned with English lyrics to ease their path into the U.S. market. Yet Mas que nada, written by Jorge Ben, became a global hit in Mendes’ rendition—one that, remarkably, retained its original Brazilian Portuguese and remains evergreen.

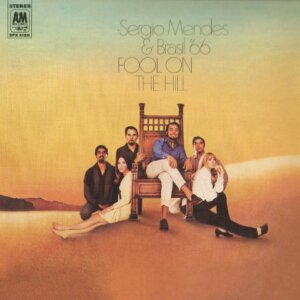

In its earliest incarnation, Brasil ’66 was a working quintet or sextet, featured on the group’s first two albums for A&M Records, the label co-founded by Herb Alpert (who would later marry Hall) and Jerry Moss. For the albums that followed, Alpert and Moss applied the same formula they had used with jazz artists like Wes Montgomery and Paul Desmond—layering in string arrangements to evoke a lush, cinematic sheen. The orchestrations, handled by Dave Grusin (soon to become a major film composer), helped produce some of the group’s most sophisticated records: Look Around, Crystal Illusions, and Fool on the Hill, the latter still a towering achievement in pop history.

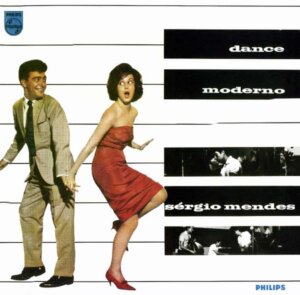

At this point, one has to ask: Did we lose a first-rate jazz pianist to the lure of pop stardom? Or did his success merely redirect an already rich career? The truth is, Sérgio Mendes began as a jazz pianist—and quite a formidable one. On his 1959 debut Dance Moderno, recorded in Rio at the age of 19 with a quintet, Mendes revealed himself to be a confident soloist, drawing dynamically from two primary models: Horace Silver and George Shearing. From Silver, he borrowed the percussive, hammering touch in the midrange of the keyboard; from Shearing—who himself explored Latin influences—he adopted the elegant propulsion of block chords. Both approaches heightened the samba’s rhythmic drive, while hinting at the polish and finesse that would characterize his later work. (Tristeza de Nós Dois and What Is This Thing Called Love show a right-hand approach even nodding toward Bud Powell.) The album made an impression, and within two years Mendes was hand-picked to join Cannonball Adderley for the alto saxophonist’s first Brazilian excursion, yielding Cannonball’s Bossa Nova—a minor album in Adderley’s discography, but a telling marker of Mendes’ emerging stature.

At the time, Mendes was seen as a rarity: a pianist deeply embedded in Brazilian musical traditions, but equally attuned to jazz and the preferences of American listeners. Record labels took note. The U.S. arm of Philips, with its immaculate stereo fidelity, spotlighted Mendes’ bossa nova skills in a series of albums that anticipated what we now call lounge. In 1963—the same year Getz/Gilberto was recorded—Philips released Quiet Nights, on which Mendes swapped samba’s exuberance for the more hushed, intimate gestures of the genre’s growing canon. If the intention was to create a kind of musical “furniture”—the soundscape for a softly lit cocktail party—Mendes and his ensemble went further, offering a result marked by professionalism, subtlety, and intelligence. The album notably adopted a Shearing-style configuration, with vibraphonist Dave Pike, guitar, and a rhythm section including longtime Mendes bassist Sebastião Neto.

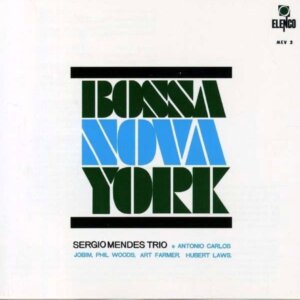

But the strongest vote of confidence in Mendes the jazz musician came from the small but ambitious Brazilian label Elenco, founded by Aloysio de Oliveira. In 1964, Elenco released what may be Mendes’ finest artistic statement: Bossa Nova York (issued in the U.S. by Atlantic as The Swinger From Rio). The lineup featured Mendes’ trio augmented by Phil Woods on alto sax, Art Farmer on flugelhorn, and Hubert Laws on flute (not all playing together), as well as Jobim himself on guitar. Four years after his debut, Mendes showed a boldness and fluency that reflected both maturity and risk-taking (Consolação stands out for its adventurousness). The varied instrumentation brought out different sides of his playing: warmth with Farmer, swing with Woods, and breezy elegance with Laws (who would later serve as a key ambassador for jazz in Brazil). Jobim—Mendes’ mentor and guide—acted as éminence grise: six of the tracks were his, including three recycled from Getz/Gilberto.

That same year, Jobim also introduced Você ainda não ouviu nada! (released abroad as The Beat of Brazil), claiming it could “open new paths in our musical landscape.” Produced by Philips Brasil and recorded in Rio, the album featured Mendes at the helm of a dynamic frontline: Raul de Souza (valve trombone), Edson Maciel (slide trombone), and Italian-Argentine tenor saxophonist Hector “Costita” Bisignani (replaced by Aurino Ferreira on two tracks). The result is a forgotten gem—pure jazz with a distinctly Brazilian soul. Arrangements by Mendes, Jobim, and Moacir Santos infuse the record with harmonic depth and vivid color, and Mendes himself shines with daring solos, particularly on the bristling Coisa No. 2.

Atlantic, recognizing his growing stature, brought Mendes into its fold, beating A&M to the punch. But this time, Nesuhi Ertegun’s golden touch fell short. The Great Arrival (1966) and Sérgio Mendes’ Favorite Things (1968) underwhelmed, despite top-tier arrangers like Grusin and Clare Fischer and lavish orchestral trappings. The first album’s cover proudly states it was “recorded in Hollywood, California”—a telling clue: the Brazil Ertegun envisioned was straight out of a movie poster. Even so, Mendes’ piano remained credible, even amid the faux-exotic trimmings. Meanwhile, Alpert and Moss negotiated permission to record Mendes with his new ensemble, as long as they used the moniker Sérgio Mendes & Brasil ’66—as if to say, “they’re not quite one of us.”

It’s worth noting that even in 1965, when Mendes recorded with vocalist Wanda de Sah for Capitol, the cover boasted “Recorded in Hollywood,” with the audacious tagline: “The greatest thing to come out of South America since coffee!” The resulting album, Brasil ’65, is a sublime bossa nova document, allowing Mendes room to stretch out and featuring a sympathetic American soloist in Bud Shank—a true pioneer in the jazz-Brazilian nexus, dating back to his 1953 work with Laurindo Almeida.

Following the massive success of Brasil ’66—and, to a lesser extent, its successors Brasil ’77, ’86, and ’88—Mendes’ career came to be defined by elegance, professionalism, good taste, and creativity. Only two albums in his catalog stand out as missteps: Love Music (1973), which plays like the soundtrack to a sun-drenched California soap opera; and the regrettable Magic Lady (1979), a disco record in every sense (released, unsurprisingly, in the wake of Saturday Night Fever). But these lapses did little to tarnish his legacy. In the years that followed, Mendes gradually re-embraced his Brazilian roots, with less concern for market trends—culminating in Brasileiro (1992), a radiant and profound love letter to samba and the culture that shaped him.

Still, one can’t help but feel a pang of regret on these pages: what a shame that Sérgio Mendes never returned to jazz with the full force of his imagination. He could have done great things.