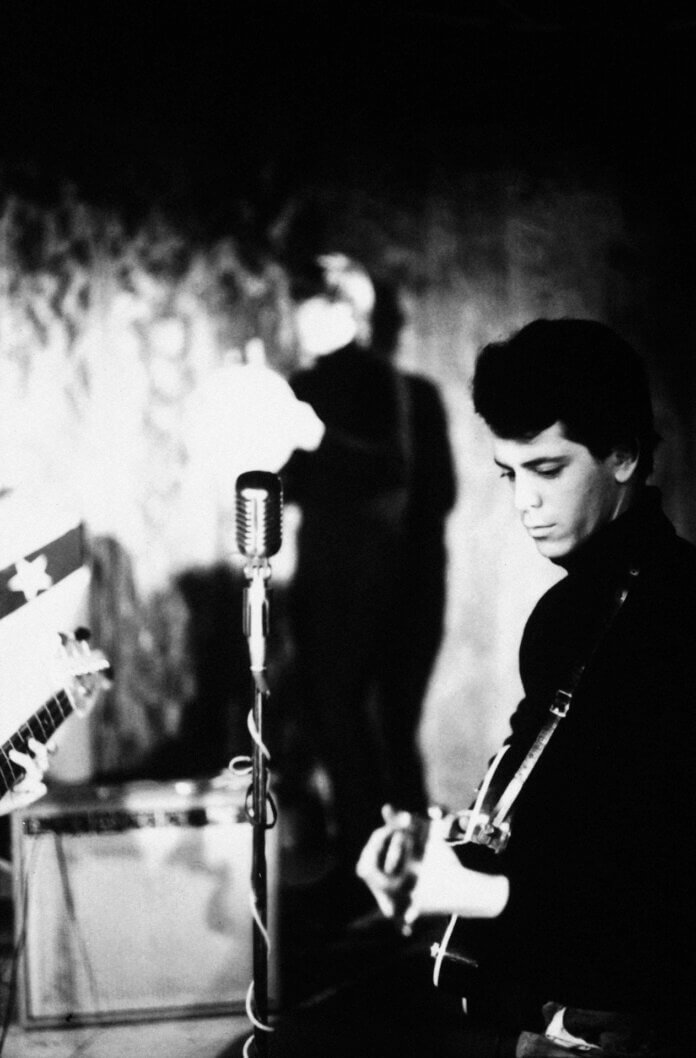

Lou Reed has been dead for eleven years – and yet, he hasn’t been forgotten, nor does anyone seem willing to let him be. His widow, Laurie Anderson, is doing everything she can to keep his already celebrated works alive and to bring to light the hidden pages still buried in the archives. A few years ago, a fascinating collection titled Words & Music was released, illuminating the murky depths where songs like Heroin, I’m Waiting for the Man, and Pale Blue Eyes were born – demos from May 1965, two years before the world would meet this brilliant, tormented storyteller and the band that formed around his and John Cale’s ideas: the Velvet Underground.

Now, those managing the Lou Reed Archives have gone even further back in time with a new CD (Why Don’t You Smile Now, Light in the Attic), revisiting the young Lewis’s earliest days as a writer, singer, and guitarist for a fly-by-night record company: Pickwick International. Pickwick specialized in tricks and small deceptions pressed into vinyl – what used to be called “bar records,” though no one seems to remember that term anymore. These were budget singles or LPs that mimicked current hits and trends, but instead of the original versions, they featured more or less clumsy imitations or pastiches. It’s the exact opposite of the world we usually associate with Lou Reed – not the visionary avant-garde, but the bottom rungs of the recording industry ladder. And yet, it’s real history, and one of the peculiar joys of this anthology lies in the contrast between the “easy listening” fare the young Reed churned out without shame and the more ambitious musical dreams he continued to nurture. It’s a useful collection, too – because, surprise, surprise, even this hackwork helped shape a great emerging talent.

Lou Reed arrived at Pickwick in September 1964. He was twenty-one, a recent graduate in English Literature from Syracuse University, where he had earned honors cum laude just that June. His first priority was to avoid the draft – mission accomplished, thanks to a nasty case of hepatitis and a few well-chosen pills taken to destabilize his psyche. His parents hoped he’d stay home and help his father with the family accounting firm, but Lou had other plans. He loved the new music – both as a listener and as a player. He’d performed with several amateur bands and had even cut a single, So Blue / Leave Her for Me, with his group The Shades at sixteen. He listened to everything, showing a particular fascination with more radical forms: in high school he’d worked as a DJ for a small radio station, where the title of his show – Excursions on a Wobbly Rail, named after a Cecil Taylor piece – said it all. A friend’s girlfriend introduced him to a young producer named Terry Philips, and Lou didn’t hesitate.

Philips, slightly older and already in a position of some responsibility at Pickwick International, was working for a label eager to grow. These were the days of Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry, Gerry Goffin and Carole King – golden-fingered composers who wrote hits in office cubicles by day and recorded them by night for the music publishing giants. Philips wasn’t in the Brill Building – he worked out of a gloomy warehouse in Long Island where 99-cent LPs and singles were stacked to the ceiling, and in one corner stood a modest recording studio with a battered upright piano and a reel-to-reel recorder. Despite the surroundings, the atmosphere wasn’t hopeless – they dreamed of better things. So Philips assembled a team of writers, singers, and guitarists. In the end, he chose three: the young Lou Reed, Terry Vance (aka Jerry Pellegrino), and Jimmy Sims (alias Jim Smith). The pay was $25 a week – all inclusive, which meant the songs these young men cranked out wouldn’t earn them a cent in royalties.

A dubious deal, but Lou took it – though he didn’t last long. Too much stress, too many restrictions: “They would lock us in a room and tell us to write ten West Coast songs and ten Detroit songs,” he later recalled. Then they’d rush them into the studio – “and in an hour or two we would record material for three or four albums.” The bands were usually credited collectively, with no individual attributions, so today it’s a matter of guesswork to determine which tracks might be Reed’s. Still, Why Don’t You Smile Now offers twenty-five surprisingly strong pieces, including tentative stabs (or should we say feints?) at abrasive rock – not an easy thing to fake. Lenny Kaye – the great rock historian and longtime Patti Smith guitarist – has written an impassioned introduction, while tireless underground chronicler Richie Unterberger has contributed extensive, meticulous liner notes.

This is a forgotten musical world – the twilight between original rock & roll and the coming sound of the 1960s, on the cusp of the British Invasion. Surf bands, Motown hits, English beat groups – Phil Spector ruled the scene with his girl groups and towering wall of sound. The mandate was clear: ride the trends. Invent long-haired Liverpudlians without passports, surfers who couldn’t swim, doo-wop crooners or fake heartbreakers – and do it fast, with no scruples. The priceless cover photo shows the four composers holding signs that sum up the Pickwick philosophy. Lou’s reads: “Don’t kill yourself to get something better.” He followed orders. Six songs from the anthology, to take the most telling example, come from a 1965 various artists compilation titled Soundsville!, a tour through the era’s hottest musical styles. There are nods to New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, England, California – surfing, hot rods, motorcycles, campus scenes – performed by the same musicians donning different hats, playing increasingly unlikely roles. The melodrama of The Hi-Lifes gives way to the garage rawness of The Roughnecks; the falsetto harmonies of The Hollywoods (naturally representing California) contrast with Jeannie Larimore’s wispy Petula Clark–like tones in Johnny Won’t Surf No More. Not all of it is trash. Reed himself makes an impression with Cycle Annie, a song about a motorcycle-riding woman interpreted by the elusive Roughnecks. For once, the roles are flipped – she rides, and Lou spins the story in the hypnotic, repetitive style that would soon define him.

These are all two-and-a-half-minute numbers – some even shorter – a clever jukebox of echoes, pastiches, and sonic sleights-of-hand. You think you’re hearing The Four Seasons – it’s actually The Beachnuts (Sad, Lonely Orphan Boy, a previously unreleased gem). Beverley Ann of We Got Trouble channels the ghost of Martha Reeves. And Phil Spector, though absent, is everywhere – evoked, desired, omnipresent – his spirit haunting songs like Really Really Really Really Really Love or Tell Momma Not to Cry.

There’s even a Pickwick tribute to The Beach Boys – a full LP of covers released under the pseudonym The Surfriders. Lou Reed would later trash The Beach Boys at every opportunity – yet here he was, plowing through their repertoire with forced doo-doo-doo cheer. In the end, the edgier material holds up best – Sneaky Pete by The Primitives already hints at the darker Velvet realm, while Wild One (Terry Philips) and Ya’ Running But I’ll Getcha (The J Brothers) seem to feature Reed on biting lead guitar.

Those months of relentless grind – from 9 a.m. to midnight, sometimes later – left their mark on the young songwriter. He knew what he wanted to write but found himself instead crafting knock-offs: “a loser Ellie Greenwich, a poor man’s Carole King,” as he put it. Then came a turning point. Philips asked Lou to write a novelty song for release as a single. Reed responded with the absurdist The Ostrich – a bizarre dance in which someone flings themselves to the floor and others stomp on them. That wasn’t the only surreal element: the track’s lurching, Louie Louie–like rhythm and fake crowd noise were topped only by Reed’s most radical move – tuning all the guitar strings to the same pitch. He dubbed it “ostrich guitar,” and the inner notes of the first Velvet Underground LP would later reference the same term, as if to underline continuity.

To record The Ostrich and promote it, Reed assembled a band called The Primitives. It included a young Welsh violist he’d recently met – John Cale, a musician affiliated with La Monte Young and Tony Conrad – and a sculptor-turned-drummer named Walter DeMaria. They’d all go on to fame, in varying forms, but this version of The Primitives was short-lived – a few scattered gigs in early 1965 across New York and the Eastern states. The single flopped, and hopes dimmed. Reed was at a crossroads – and, thankfully, he took the right turn. He walked away from Pickwick and chose to move forward with Cale, focusing on the demos he’d just recorded and dedicating himself to the songs he truly believed in – in the sonic language he had chosen, no matter how difficult.

He would be lucky. Soon, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker would join. The Velvet Underground would be born. Andy Warhol, Nico, the banana album, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable – all that once seemed excessive now reads like history. And it is – it is history.