Just a few months ago, Jack DeJohnette wrote on his Facebook page that one of the defining moments of his musical growth was seeing Sly & the Family Stone perform live in 1969. He wrote:

“Sly is an innovator who influenced so many artists, such as Miles, myself, Prince, and Herbie Hancock, to name a few of the musicians he touched so deeply. Sly changed the sound and shape of new music!”

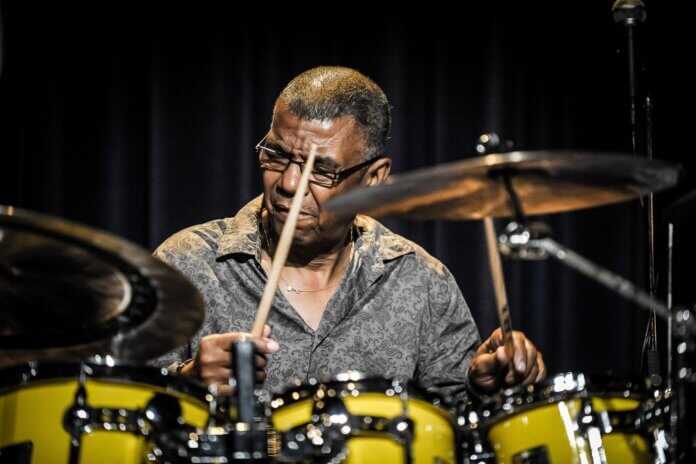

DeJohnette was one of the great masters of jazz drumming. Yet his strictly jazz-related achievements often make us forget that he experienced firsthand the seismic shifts in the musical landscape of the mid-to-late 1960s, as did many of his peers. Born in 1942 – three years before Tony Williams, with whom he shares many similarities – DeJohnette played a crucial role in Miles Davis’s evolution, as evidenced by his work on Bitches Brew and with Davis’s subsequent groups, culminating in the legendary 1970 band with Gary Bartz and Keith Jarrett.

To truly understand DeJohnette’s multifaceted musical world, one must set aside the rigid categories so beloved by “true jazz” purists and recognize that the drummer, pianist, percussionist, vibraphonist, singer, and composer was a child of an era that blended free jazz, rock, and R&B. This gave the most open-minded and adventurous musicians the freedom to draw on disparate elements – even seemingly incongruous ones. DeJohnette was influenced as much by Miles Davis as by Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone. It is both unrealistic and limiting to seek the dominance of one figure over another in his music.

This fluid, borderless spirit is even more evident in DeJohnette’s work as a leader. He released around thirty albums under his own name, an output marked by remarkable intensity. It is perhaps less visible in his prestigious collaborations – from John Coltrane to Charles Lloyd, from Miles Davis to Keith Jarrett, and countless others – but even there, his eclecticism was never superficial or mannered. Critics sometimes misread this eclecticism, but DeJohnette embraced it as a gift, never a burden.

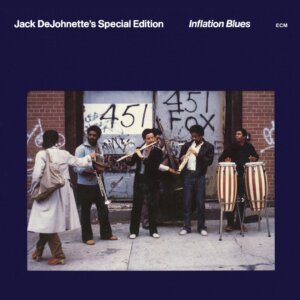

For that reason, it seems fitting to honor Jack DeJohnette with a track that may seem unusual yet is fully consistent with his artistic vision: Inflation Blues, recorded in 1982 for ECM on one of his most overlooked albums of the same name. The piece updates its original 1971 version, which appeared on Columbia’s Compost album. Compost was not only the title of the record but also the name of the band, a short-lived ensemble that produced two albums and featured Bob Moses on drums, Harold Vick on saxophones, Jack Gregg on bass, and Jumma Santos (also known as Jim Riley) on percussion. Santos/Riley, incidentally, had been one of the “alumni” of the Bitches Brew sessions.

On Compost’s first album, DeJohnette played vibraphone and his beloved clavinet – and, notably, he also sang. Inflation Blues was sung by DeJohnette and began life as a rock-blues tune infused with strong soul overtones.

A decade later, however, he completely transformed it into a reggae–dub piece. In this 1982 version, Rufus Reid and DeJohnette take on the roles of Sly & Robbie: the drummer sings, overdubs the clavinet part, and drives the rhythm section, while Baikida Carroll, John Purcell, and Chico Freeman handle the horns. It wasn’t his first venture into Jamaican territory – a few years earlier, he had recorded the whimsically titled Malibu Reggae on the ECM album Untitled, with Alex Foster, Warren Bernhardt, John Abercrombie, and Mike Richmond. The result was deliberately quirky: a kind of unstable lounge music, reminiscent of Carla Bley and Steve Swallow’s mid-1980s experiments (Heavy Heart, Night-Glo, Sextet) – halfway between satire and nightclub irony.

Here, though, DeJohnette is utterly serious. He shows us how, for him, Black music has always been a single entity, regardless of its source.

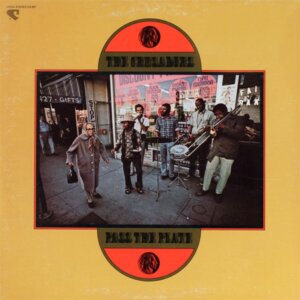

Perhaps this also explains the album’s cover image, showing the musicians playing on a sidewalk while accepting a coin from a passerby – a deliberate reference to the 1971 Crusaders album Pass the Plate. The only difference is that, in DeJohnette’s photo, the passerby offers her donation quickly, while the grim old woman on the Crusaders’ cover looks as if she has no intention of giving anything at all.

Luca Conti