Darius, you’ve dedicated much of your life to demonstrating how jazz can shift social consciousness. Looking at the world today, do you feel you’ve succeeded in that mission?

I never really set out with a grand global ambition. Jazz was already deeply tied to the political struggle in South Africa, and our bands simply carried that intention forward. When I toured Poland in 2018—sixty years after the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet’s groundbreaking tour behind the Iron Curtain—I saw firsthand how meaningful those concerts had been for people living under political repression. A 1958 Dave Brubeck program is displayed in the very first case at the Solidarity Museum in Szczecin. In 1988, my wife Catherine and I brought the first multi-ethnic student jazz band out of South Africa—the Jazzanians—which made headlines across U.S. national networks. That project sparked a commitment to continue forming student bands that could serve as living models of what a post-apartheid South Africa might look like.

Do you believe jazz remains the most powerful language for confronting racism and apartheid?

Jazz, by its nature, expresses freedom, collaboration, and dialogue. It’s improvisational, cooperative, and inherently inclusive. It has always resonated in places where societies are struggling with injustice—starting with the U.S., but also in countries like Poland and South Africa.

In 1983, you founded what many consider to be the first university jazz program in Africa. How did that come about?

Strictly speaking, I didn’t found Africa’s first jazz university, but I did establish the first formal jazz studies program at the University of Natal in Durban. The head of the music department at the time, Professor Christopher Ballantine, knew my wife and encouraged me to apply for a vacant music theory post, with the intent of turning it into a jazz position. Many of today’s leading South African jazz musicians came through that program. Then, in 1989, we established the Centre for Jazz and Popular Music, which is now internationally recognized.

What lasting lessons did you take from your years in South Africa?

Living under apartheid made me far more politically aware. Our multi-ethnic bands weren’t just musical projects—they were political acts. I came to understand that people who resist injustice are among the most extraordinary individuals you’ll ever meet.

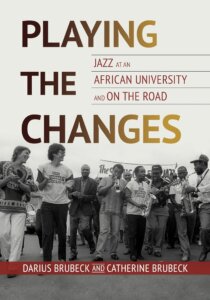

How did the idea for your book Playing the Changes come to life?

My mother, Iola Brubeck, kept everything—letters, programs, photos, newspaper clippings, flyers—we sent home from South Africa. Every time we visited, my parents urged us to write a book. They were fascinated by our stories and enjoyed hosting many of the students we brought to meet them. They formed friendships with people like Victor Ntoni, Barney Rachabane, Zim Ngqawana, and other members of the Jazzanians. The idea for the book had been with us for years, but we began writing seriously in 2017 thanks to a generous residency grant from the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), which we received twice. That support gave us both the time and the responsibility to finally bring the book into being.

Your father’s legacy casts a long shadow. You’ve often spoken about carving out your own space. Do you feel you’ve succeeded?

Of course I’ll never achieve what my father did—no one could. But I believe I’ve made a meaningful contribution, particularly in the field of jazz education. I’ve also led my own group, the Darius Brubeck Quartet, for over 17 years now, and we continue to tour internationally. A documentary, Playing the Changes: Tracking Darius Brubeck, is currently in production and will be screened at several film festivals.

What were the most important things your father taught you?

Both of my parents were deeply engaged with the arts and believed that being an artist also meant being socially aware. Musically, my father was my first and strongest influence—but I’ve had many others too. The result is a synthesis of different eras and genres that emerges in my own playing and composing.

Music, and jazz in particular, has always been a very personal matter for the Brubeck family. How has it shaped your identity and your relationships?

Jazz has been a unifying thread. We’re all on the same wavelength and don’t need to explain ourselves to one another. In July 2024, I performed with my brothers again—our first recording together dates back fifty years. We live in three different countries and have separate careers, but the family “business” remains a kind of home base for us all.

In what way does your identity influence your creativity?

If you mean the Brubeck name and legacy—it definitely sets a standard. I want everything I do to reflect the same sense of integrity that people associate with that name.

Jazz has evolved dramatically—incorporating electronics and blending with other genres. Do you view these developments positively?

Whenever I feel hesitant about new directions in jazz, I remind myself that decades ago I was experimenting with synthesizers, free jazz, and Indian classical elements. Every generation reinvents the music in its own way. Whether I like all of it or not isn’t the point. Jazz has always been a glorious hybrid—it’s global, and that’s why it endures.

You also spent time in Turkey. What did you take from that experience and from touring with your father?

I held a Fulbright teaching position at Yildiz Technical University and found the students incredibly open to jazz. I also loved diving into traditional Turkish music. My father’s Blue Rondo à la Turk is a perfect example of East-West fusion—it came out of the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s 1958 tour of Turkey, long before the term “world music” existed.

What are your current goals as a jazz musician and educator?

To keep improving as a player, to find more time for composition. Though I no longer teach full-time, I still attend jazz conferences and hope to write more about the music and its history.

What drives your creativity? Derek Bailey once described improvisation as the search for infinitely transformable materials. In 2024, what do you find particularly inspiring?

I love that quote, but I might flip it: I think the process starts with something infinitely transformable—like the blues. Improvisation allows endless variation. There’s nothing specific in 2024 that’s reshaped my work. My creative impulse still comes from a love of the process itself—being sparked by an idea, an image, an emotion, even a simple musical phrase.

What are the core ideas behind your approach to music?

Storytelling, evoking emotions and meaning beyond the notes themselves. I never strive for musical “purity”—there’s always something else mixed in. Some musicians are silent about what their music means, and I respect that, but I want mine to carry meaning. That requires clarity—when I compose or perform, I have to know what I’m trying to say.

Finally, what’s next for the Brubeck Institute—and for you—that people might not know?

The Brubeck Institute has evolved into the Brubeck Living Legacy, a non-profit that organizes the annual Brubeck Jazz Summit at Lake Tahoe, funds scholarships through the Jazz Education Network (JEN), and will soon award a new prize at the Royal Academy of Music in London. That award will allow a student to record a debut album with the Ubuntu Music label. The Legacy has also supported South African musicians performing at Jazz at Lincoln Center and other New York venues.