The New York Times has described it as “one of the greatest music festivals in the world.” We agree completely with the renowned newspaper; after all, we have closely followed the festival for years and reported on it in these pages. Big Ears is a unique event bearing the unmistakable mark of originality. This four-day musical extravaganza takes place in Knoxville, Tennessee, a town that would otherwise have slipped into obscurity among the many other towns in the southern United States. Ashley Capps, the creator of this musical extravaganza, is one of those rare individuals who emerge from the depths of history and have the ability to create something significant from nothing. Or, if not exactly out of nothing, then out of the cocktail of feelings that drive great ideas: passion, invention, and stubbornness. Let’s add culture to that list, too.

During those four days at the end of March each year, the otherwise peaceful Tennessee town – already renowned for its excellent whiskey and home to American music capitals such as Nashville and Memphis – is turned upside down. Hundreds of musicians, ranging from famous artists to unknown talents, perform at around fifteen venues, from small clubs to large theaters. They showcase every musical style, from country and folk to rock, jazz, blues, classical, and contemporary avant-garde. Country, folk, rock, jazz, blues, classical, and contemporary avant-garde all have a place, as well as a large, attentive, and appreciative audience.

For several years now, the festival has sold out before it even begins. Considering that there are no tickets, only day passes or passes for the entire festival – which are expensive in a place where even hotels are not cheap – I think it takes a magic wand for this to happen. The organization is practically perfect from technical and logistical points of view. I never heard any sound problems at the concerts, and detailed information is provided on a series of events that often take place simultaneously from noon (sometimes even 10 a.m.) until midnight every day.

The only drawback is that there are no taxis and public transportation is scarce. You have to walk miles to get from one concert to another, sometimes running. You have to be physically fit to go to Big Ears!

This year’s edition, the sixteenth, featured more events, including debates and meetings with musicians, in addition to concerts. There was a greater emphasis on quality jazz, rock, and pop compared to contemporary music and folk, which were more prevalent in the past. While there were few notable musical innovations, there were many interesting concerts, some of which were sublime.

The following are definitely worth mentioning among these: the psychedelic rock band Yo La Tengo; guitarist Nels Cline in two different lineups; the Philip Glass Ensemble; flutist Claire Chase; trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, both solo and with his new project; bluesman Taj Mahal; and the Sun Ra Arkestra.

The electrifying atmosphere of Big Ears undoubtedly contributed to the excellence of certain performances. The Arkestra, named after Sun Ra, performed wonders unseen in years despite the absence of Marshall Allen. Allen, 101 years old and understandably unable to travel, continues to lead the band with his saxophone.

The festival culminated in a concert featuring the orchestra and Yo La Tengo. The two bands on stage at the large Civic Auditorium were a unique spectacle – in a class of their own, and practically impossible to reproduce elsewhere. Some may have found the concert chaotic or even orgiastic, but the two orchestras ultimately sublimated their underlying hypnotic character. This may have been a deliberate nod to the festival’s overall meaning. Let yourself go in the labyrinth of sound without losing sight of music’s ultimate meaning and primordial beauty.

Two figures captured the audience’s attention, astonishing even the connoisseurs: First, Ira Kaplan, Yo La Tengo’s lead guitarist. On stage, he seems like a dissected and illogically reassembled Jimi Hendrix in search of ever-more-extreme sounds. His interaction with bassist and keyboardist James McNew is also impressive.

Then there was Arkestra singer Tara Middleton. With her powerful and sinuous vocals, she appeared like a Carmen Miranda on acid – irresistible. Her performance of “Stranger in Paradise” sent Alexander Borodin into hyperspace alongside a pulverized Tony Bennett. Adorable.

Both bands did something extra in their individual concerts that is rare to hear today: they elevated kitsch to an art form of pure beauty. This demonstrates that they have enviable control of their instrumental technique, along with their obvious creativity.

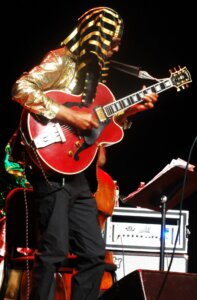

With a more serious demeanor but equally incisive intentions, Nels Cline appeared back in vogue after a few years’ absence. He showed up at Big Ears with two bands: his “classic” Nels Cline Singers and the new Consentrik Quartet. The album recently released on Blue Note is definitely not to be missed. In both cases, we heard some of the best music at Big Ears.

Cline is certainly one of the greatest guitarists around. He can push himself to the extreme in his search for sound with his Singers sextet – who, for the uninitiated, are instrumentalists of rare skill, not singers – to the point of becoming a perfect double of Ira Kaplan. Or he can engage in intricate jazz structures with maniacal perfection of language with Consentrik, where he is joined by the talented saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock, double bassist Chris Lightcap, and drummer Tom Rainey. The quartet works like a Swiss watch – absolutely perfect.

This time, the same cannot be said for Bill Frisell, another great guitarist, who appeared at the festival with his new project, In My Dreams, and with Charles Lloyd in tribute to the late Zakir Hussain.

I hope Bill will forgive us for feeling a bit bored whenever he calls on violinist Jenny Scheinman. Despite her undeniable talent, she tends to follow well-trodden paths. In fact, the band could be called In My Sleep, despite the return of Hank Roberts and Tony Scherr. With Lloyd, the memory of Hussain, despite good intentions, amounts to little more than a confused and blurred mélange, further weighed down by the monotonous and somewhat plaintive voice of Indian singer Ganavya. This is despite the consistently brilliant and precise saxophone solos. It’s a shame because these two masters have created wonders in many other situations.

Much better is the rough but good-natured guitar playing of Taj Mahal, the legendary bluesman who, in his old age, appears even more vital and – if we may say so – more profound than in his youth. Accompanied by a fine group of musicians, including the powerful Hawaiian steel guitarist Bobby Ingano (who gave a splendid interpretation of the classic “Sleep Walk”), Mahal enjoyed himself and entertained everyone with his “happy blues.”

In these songs, the desire to transform the usual dramatization of that musical language into joyful communication prevailed without becoming a parody. This is something difficult to achieve, but he found a unique form of expression.

In contrast, the concert by the trio of funk masters – formed by bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma, guitarist Vernon Reid, and drummer Calvin Weston – fell into the trap of egocentrism, repeated to the point of exhaustion despite their good intentions.

Returning to more refined jazz, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire’s new project with a string quartet, Honey from a Winter Stone, seemed overly ambitious in its desire to combine different musical languages in a single work. The music is undoubtedly high quality, but ultimately, it lacks the lyrical and poetic tension usually found in a talented trumpeter.

We preferred his solo concert, where the solipsism of the trumpet did not devolve into cold mannerism but rather into a relentless pursuit of an intimate and profound sound. However, it must be said that the album Honey from a Winter Stone is more successful and is perhaps one of this year’s masterpieces. Therefore, the theater performance must have suffered from a lack of rehearsal, which would have been useful.

The same could be said of the quartet brought together by the revived drummer Barry Altschul from the golden years of free jazz, along with the young Braxton. Despite the presence of three aces – Uri Caine, Mark Helias, and Jon Irabagon – the performance ended up being lopsided.

On the other hand, Steve Coleman, Tyshawn Sorey, Vijay Iyer, and Wadada Leo Smith gave their all in their respective stylistic fields with diligent professionalism. Meanwhile, Steve Lehman’s quartet, featuring Mark Turner in homage to Anthony Braxton the composer, delivered one of the most beautiful and intense performances of the entire festival. It deserved a theater instead of a small club, but that’s okay given the endless digressions that Big Ears imposes on those who want to see as many concerts as possible.

We end on a high note with contemporary music, thanks to two excellent concerts. The Philip Glass Ensemble, conducted by keyboardist and devoted Glass interpreter Michael Riesman, performed Glass’s Music in Twelve Parts, his masterpiece, in two sessions. The performance was absolutely flawless.

Hypnotic as always, the American composer’s music rises above formal austerity to reach heights reserved for a few composers in the last sixty years. It bounces ecstatically, and will continue to do so for at least the next two hundred years.

Our only criticism of Glass is his excessive output of symphonies, operas, soundtracks, etc., with the ever-present risk of hagiographic repetition. However, Music in Twelve Parts remains one of his most beautiful compositions.

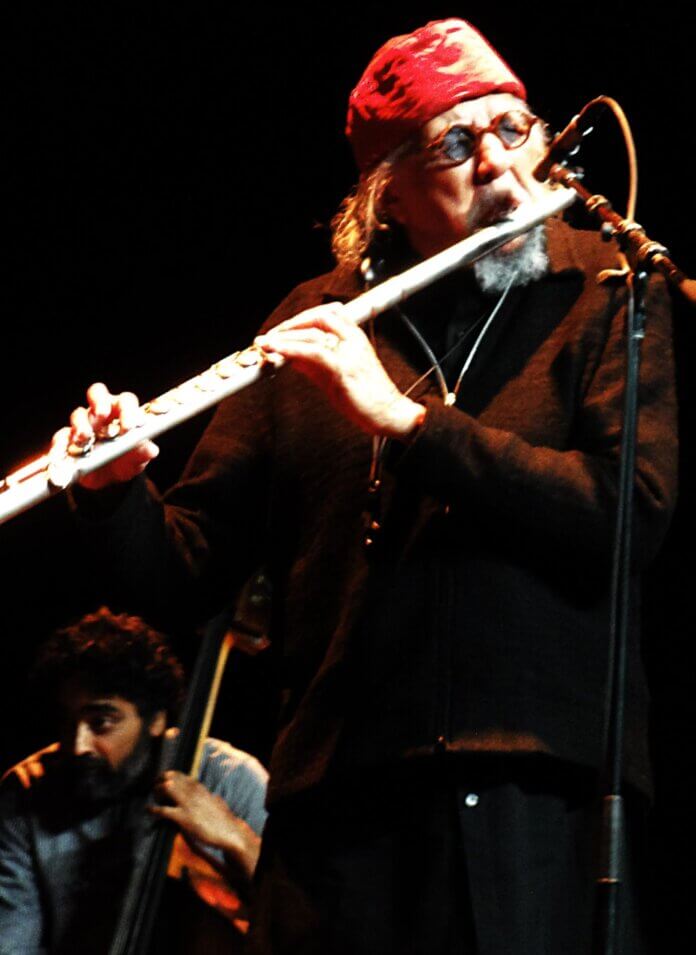

Finally, flutist Claire Chase and the Mivos string quartet offered a heartfelt tribute to another great minimalist, Terry Riley, entitled The Holy Liftoff. The long, uninterrupted suite lasts more than an hour and is woven together with a series of counterpoints. However, there are variations in tempo and non-obstinate repetitions of themes, gently separated by Riley’s own recorded voice.

Chase carved out numerous solo passages for herself within these structures, using different types of flutes and maintaining a strong expressive intensity throughout. It was a tour de force for her and the other members of the string quartet, leaving the audience breathless.

With Chase performing, no superlatives would suffice to describe her technical skill, exceptional interpretive quality, and the emotion she brings to music that requires absolute rigor. She is undoubtedly one of the greatest flutists on the planet today. Each time she performs, she confirms her status as an astonishing musician.

Throughout this review of the festival, we deliberately omitted some concerts that were not outstanding, along with many others that we would have liked to attend but were unable to due to time constraints and the limitations of the human body.

What can we say about an eight-hour solo organ performance in a church or a popular young pop singer performing for an enthusiastic audience with songs about lost and perhaps found love?

We won’t mention any other names, but then again, this is Big Ears – a crazy musical romp where you can’t see everything, but what you do hear is worth much more than at many other festivals.

This could be a lesson for Italy – we’re happy to suggest it. Sometimes, quantity and quality go hand in hand; you just need courage and passion.

And we’ll say it again: Culture.