If there were a ranking of the best rhythm sections of all time, the duo of Barry Altschul and Dave Holland would be at the top of the list. It would be a well-deserved recognition for this pair of aces who, together with Anthony Braxton, were able to write some, even many, of the most important pages of jazz in that decade. A strange Anglo-American pair, made up of two white guys, comparable only to the men of the Art Ensemble of Chicago and a few others. Very close, both since they were kids, busy listening to music and trying to play it. This was the case with Altschul, according to what Robert Palmer wrote in the liner notes to “Another Time/Another Place,” the second album the drummer (but perhaps it’s an understatement to define him as such) made in the role of leader. In fact, the young man from the Bronx, born in 1943, enjoyed listening to latin and black music as well as the classical music he heard at home. His high school teachers confirmed that young Barry did nothing else. He studied drums with Charlie Persip, who had worked with Gillespie, and eventually left home when he decided to try to become a professional musician, over the objections of his parents. Released in 1978, “Another Time/Another Place” had a first and last reissue five years later, still in LP format, and then finally and inexplicably disappeared from the catalog. Altschul came to this record – and the one before it – with a prestigious resume, to say the least. In his twenties, he met Paul Bley by chance, who brought him into the original Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, originally the Jazz Composers Guild, and gave him a spot on the star-studded “Communication” that saw the light of day in 1965. In addition to Peacock, Bley was joined by several double bass players, from Kent Carter to Steve Swallow and Mark Levinson. Holland, who had just put his signature (and with it Corea’s) on a milestone like “Bitches Brew,” completed this waltz of couples.

The trio was formed in 1970 and met in the studio on April 7 and 8 to record the tracks for “The Song of Singing”, released the following year on Blue Note, an album in which Corea returned to the acoustic piano after his first electric shock with Davis. The result was a record full of free shaking, melodic lines and rarefied atmospheres. The set list included all the compositions of the trio or individual members except Wayne Shorter’s Nefertiti, which Corea had never played during his two years with Davis but which became a signature piece of the future Circle (they also played it in Bergamo in 1971). The record immediately brought the newly formed trio gigs, and it was at one of them, at the Village Vanguard, that Jack DeJohnette introduced Corea to the very young Braxton. It was a short step from that meeting to an invitation to join the trio. Circle didn’t last long, but it left a deep mark. Between concerts and various recordings, always for Blue Note, they began to trace some of the most interesting musical directions taken throughout the seventies, the search for a balance between improvisation and tradition, which Braxton in particular would cultivate and reap the best rewards. Then it was time to move on to ECM, which first brought the original trio into the studio to record the album “A.R.C.,” which opened with a new version of Nefertiti, and then captured the quartet in action in Paris on February 21, 1971 (in a medley that included Shorter’s song again), and in no time at all, Circle broke up. In no particular order, its members also play with Braxton on “The Complete Braxton,” recorded in February 1971, Corea alone and the rhythm section on other tracks. After the quartet broke up, they all initially stayed in Manfred Eicher’s house, but the pianist went his own way, writing the first chapter of Return to Forever with the album of the same name, while the other three went into the studio to record Holland’s debut as a leader, the imaginative Conference of the Birds. Here Altschul’s mastery was on full display in his use of the full range of timbres and multiple rhythmic solutions, sometimes reinforcing his partners’ interventions, sometimes emphasizing them, or, on the contrary, seeking to enhance them by fragmenting their path. His sonic palette has expanded exponentially, and his marimba solo on the track of the same name pulsates with life today as it did yesterday. Another volcanic personality, at least in those years, participated in the album: Sam Rivers, who was about to explode after some illustrious experiences (especially the album with Davis, “Miles in Tokyo”) that had left him rather in the shadows. His appearance at the Montreux Festival, documented by “Streams”, caused a sensation. After that, Altschul played several times, sometimes with Holland, in various trios formed by the Oklahoma multi-instrumentalist over the course of the decade, keeping himself busy while remaining committed to the Braxton Quartet, as did his English partner. In fact, after “Conference of the Birds,” Altschul continued to work with Rivers, releasing a couple of albums as a duo on IAI, Bley’s label. A series of encounters, many of which have been documented in recent years by the Lithuanian label NoBusiness Records with the launch of the Sam Rivers Archive Series, which currently consists of six volumes. As for the achievements of the Braxtonian groups, first with Kenny Wheeler and then with George Lewis, there is nothing more to add to the rivers of ink that have been spent praising their value. Milestones were born, “Five Pieces 1975”, “New York, Fall 1974”, “The Montreux/Berlin Concerts”, records that also confirmed Altschul’s percussive mastery, his ability to emphasize all the possible sounds of his instrument. In fact, when the brilliant Braxton Quartet disbanded after almost a decade of amazing collaborations (Roswell Rudd, Andrew Hill, Julius Hemphill, Pepper Adams), the indefatigable Altschul decided that the time had come to go it alone, without completely abandoning the role of partner in other people’s projects.

He made his debut with “You Can’t Name Your Own Tune,” released on Muse, a label founded by Joe Fields in 1972. To create it, he called on a top-notch group of musicians. He reunited with Holland and George Lewis, with whom he had already worked with Braxton, and also recruited Rivers and one of the founding fathers of the AACM, pianist Muhal Richard Abrams. It was a brilliant debut, also thanks to the well-rehearsed interplay, and much of it came directly from previous experience: as can be seen from the opening track, the eponymous piece, a jaunty free-bop with a compelling solo by Holland wedged in the middle of the composition, where even Rivers’ contribution leaves its mark. A change of mood marks the rest of the album. It begins again with the funereal tempo of the (piano-less) For Those That Care, characterized by the spirited interweaving of flute and trombone, supported by Holland’s methodical work with the bow and the leader’s discreet management of pauses and reprises. This is followed by a very ramshackle swing that bounces along Natal Chat and only manages to straighten out in the finale. The second side featured a composition by Abrams, Cmbeh, another example of crystalline free bop, all based on a piano ride that was at times furious and at others fluid, accompanied by a rhythm section that galloped along just as fast, with Holland carving out a second memorable solo. Altschul also took the opportunity to solo on the following Hey Toots!, using the entire percussion set at his disposal, including the waterphone, a 1973 patented idiophone with a sometimes disturbing sound. Once again, Altschul showed off his well-stocked arsenal of sounds, including a fabulous gong stroke midway through, just before the voice of the waterphone is heard. To close the record, he chose a piece by Carla Bley, King Korn, performed by the full quintet. One acrobatic feat after another, between anger and joy, a series of solos that gave shape to a crackling version.

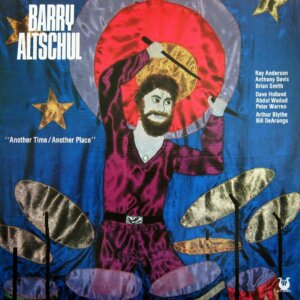

“Another Time/Another Place”, released the following year and currently out of print, did not suffer the same fate. But it is not a second-rate work, nor are the new partners chosen to record it. In addition to the ever-present Holland, Arthur Blythe on alto, Ray Anderson on trombone, Anthony Davis on piano, and another double bass player, Brian Smith, made their contributions, while Abdul Wadud and Peter Warren took turns on cello and guitarist Bill DeArango, then nearly sixty, an early bopper who, like Persip, had experience with Dizzy Gillespie. Fresh forces, which Altschul distributes in different measures in the songs of the line-up, but which you never hear all together.

Altschul’s intention was to give life to a new course after having metabolized his thousand and one experiences. A synthesis of yesterday and today, manifested in capital letters by the medley that took up most of Side A, Crepuscule: Suite for Monk, which brings together three very famous pieces, arranged by Anthony Davis with a Monk-like spirit and a personality that is more a product of the times. Between fidelity and betrayal, with space for improvisation and just as many passages that were pure bop, penetrating solos (Davis and Blythe’s were superb in Crepuscule with Nellie), the high speed of the rhythm section (here Brian Smith on double bass), the agile support of DeArango, the homage succeeded precisely because of the balance between original compositions and overall re/composition. To close the side, they played Chael, a piece composed by Davis that recalls the more chamber and free style of the Circle. The piece with Altschul features only Davis and Abdul Wadud on cello, and the dialogue between the three is very tight, tense, at times abstract, rich in color, punctuated by silences, vibrant and abstract at the same time. An excellent performance, supported by excellent technique from all. On the second side, the dance is opened by the short Traps, another solo excursion of Altschul, even more effective than Hey Toots! on the previous album, on a more exquisite percussive level, a real drum solo in which he also shows his muscles in an unusual way. An interlude before moving on to Pentacle, written by Holland, a majestic mosaic in constant change, an interweaving of strings (two double basses and as many cellos at work) marching towards darkness, the conclusion of which is another show by Altschul, who also reuses the waterphone, then steps aside to leave the field to a riot of dancing bows and solitary melodic lines. A journey through time closes the album, for in the piece of the same name, written by Altschul himself, there are many latin rhythms and even echoes of the swing era (thanks to Anderson’s sparkling trombone), echoes of childhood listening, perhaps, as much as free shivers, along a trajectory full of sudden curves, traveled with constant changes in tempo. Altschul has never stopped since then, even if he has had moments of decline. A new trio with Mark Helias and Ray Anderson (Brahma) is worth mentioning, and today, at the age of eighty-one, he is still able to hold his own on stage, not only recording in the studio but also giving concerts. Proof of this are his recent efforts with the OGJB Quartet (with Oliver Lake, Graham Haynes and Joe Fonda), with whom he paints sounds on an abstract canvas, and the trio 3dom Factor, also with Fonda and saxophonist Jon Irabagon, a fierce group that glides with ease from more swinging situations to others that are more wildly free. On the other hand, this beautiful record, which, as its title suggests, needs another place and another time to be reissued, is stuck at the post office. We hope to see it.