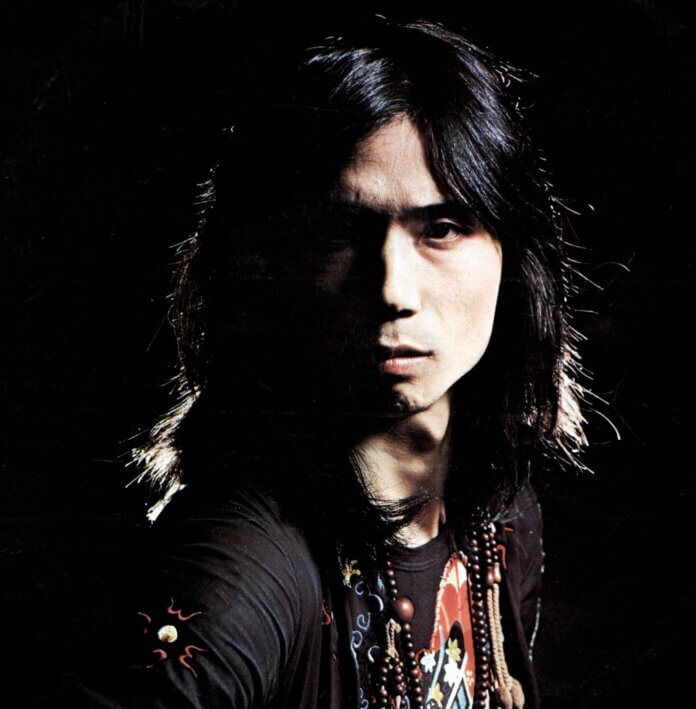

It is not uncommon to encounter the vicissitudes of multifaceted and virtuosic musicians who burst onto the scene with a vengeance, garnering consensus from many quarters, only to gradually fade into the background, or at least escape the attention of the media and the public. This is certainly the case with the Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamash’ta (born Tsutomu Yamashita, Kyoto, 1947), who in the 1970s achieved a certain level of fame even among jazz-rock and progressive music aficionados. Already as a teenager, Yamash’ta had shown a prodigious talent, so much so that at the tender age of sixteen he distinguished himself as a soloist of the Kyoto Asahi Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by his father in the performance of Darius Milhaud’s Concerto pour marimba, vibraphone et orchestre op. 278, which also attracted the interest of the Armenian-Georgian composer Aram Chatchaturjan. In 1964 Yamash’ta took his big chance. A meeting with timpanist Saul Goodman after a concert of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in Kyoto inspired him to move to New York to attend the Juilliard School. His subsequent studies at Berklee College in Boston brought him closer to the world of jazz, without preventing him from keeping a foot in both camps. His collaboration with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Seiji Ozawa in 1969 and his subsequent contributions to Hans Werner Henze’s El Cimarrón (1970) and Prison Song (1972), to his compatriot Toru Takemitsu’s Seasons (1972) and to Peter Maxwell Davies’ Turris Campanarium Sonantium (1971) clearly demonstrated this.

For this reason, too, the first half of the 1970s represents a period of feverish activity and, at the same time, a turning point in the career of the young and talented percussionist, who was eager to experiment and to measure himself against several languages. Let us first examine his jazz interlude. Two very different works from 1971, but they have in common the inexhaustible and creative use of a wide range of percussion instruments. Metempsychosis” (Columbia) is a joint project with the pianist and composer Masahiko Satō, realized with a Japanese instrumentation of seventeen elements: five saxophones, four trumpets and as many trombones, as well as a rhythmic ensemble of double bass, drums, percussion and piano of the two principals. A frenetic, iridescent percussive carpet serves as support for the rarefied percussion, followed by tensions and explosions in pure free style that in some ways recall the contemporary experiments of Globe Unity. Red Buddha” (King) is a percussive soliloquy – between pure improvisation and classical-contemporary suggestions (Xenakis?) – divided into two suites. Yamash’ta makes the most of a wide range of percussive instruments, including vibraphone, marimba and steel drums.

1972 marked Yamash’ta’s arrival in England and fruitful contacts with the British jazz-rock scene, as well as the signing of a contract with the Island label. The result was a fruitful collaboration with the trio Come To The Edge, consisting of Scottish percussionist Morris Pert (a classically trained member who would later contribute to the jazz-rock group Brand X and collaborate with many rock and pop musicians), bassist Andrew Powell, and multi-instrumentalist Robin Thompson (electric piano, organ, and soprano sax). Floating Music” is a good example of the meeting of two cultures, thanks to the scales, hypnotic thematic cells and variety of timbres and rhythms contributed by Yamash’ta. The interaction with Pert, the ethereal use of the vibraphone, and Thompson’s use of the sho (a traditional Japanese free-reed instrument) on One Way stand out. A horn section (soprano sax, trumpet and trombone) is added on Keep In Lane, while bassist Phil Plant replaces Powell on two tracks. The opener Poker Dice features pianist Peter Robinson on Fender Rhodes, who later formed the trio Sun Treader with Pert. The latter, along with Robinson and bassist Alyn Ross, formed the nucleus of Red Buddha Theatre, the protagonist of The Man From The East, recorded in 1972 but released the following year. It is an expanded line-up with a large contingent of Japanese musicians (including Hisako Yamash’ta, violinist and wife of the percussionist) and some British guests, such as Anglo-Indian guitarist Gary Boyle, formerly of Brian Auger’s Trinity and later founder of Isotope. The music, composed specifically for the show, is partly inspired by noh and kabuki theater and skillfully blends traditional melodies and elements (see the use of the shamisen, the three-stringed lute) with an edgy, no-frills jazz rock.

The relationship with Island was consolidated over the next three years, although Yamash’ta gradually turned to more predictable and commercially successful formulas. In 1973, he formed the group East Wind, which included his wife and Boyle, as well as Hugh Hopper, the formidable bassist who had emerged from Soft Machine, and keyboardist Brian Gascoigne. Freedom Is Frightening” is the first fruit of this new endeavor: a full-bodied, nervous jazz-rock – also thanks to Hopper’s distortions and Boyle’s microtonal, John McLaughlin-esque approach – based on changing metrics. The percussionist works mostly on drums, overdubbing here and there. The album closes with the delicate Wind Words, for violin, acoustic guitar, vibraphone (played by Gascoigne) and rarefied metal percussion effects. Later, the same group recorded the music for the soundtrack of One By One, a documentary about motor racing. This was not entirely new for Yamash’ta, who in previous years had worked with Peter Maxwell Davies on the soundtrack to Ken Russell’s The Devils and with John Williams on the soundtrack to Robert Altman’s Images. In 1975, Raindog suffered a major setback. Although East Wind formally still existed, with Hisako, Gascoigne and part of Boyle still in the band, the recording session featured some fairly anonymous Japanese instrumentalists and the voices of Maxine Nightingale and Murray Head. The music inevitably flattens out into a mixture of mannered jazz-rock, progressive and pop.

This is a sign that anticipates the pharaonic project developed by the percussionist in 1976-1977: the constitution of the supergroup Go! with Steve Winwood (keyboards and vocals), Klaus Schulze (synthesizers), Al Di Meola (guitar), Michael Shrieve (drums) and Paul Buckmaster, responsible for the arrangements and the direction of a string section. Go!”, “Go Live From Paris” and “Go Too” document a mammoth mechanism in which incompatible styles and talents converge. So much so that this elephantine creature, undoubtedly the result of a commercial operation, ceased to exist within a few years. In the early 1980s, after returning to Japan, Yamash’ta embraced Buddhist philosophy and devoted himself to electronic compositions reminiscent of New Age and Tibetan chanting, more in keeping with the spirit of his culture and far from despicable. He virtually disappeared from the Western music scene. A phenomenon of rejection? Probably, but with dignity.